From coast to coast, groups of people have sprung up to protect members of their communities as Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Border Patrol agents threaten them with brutal enforcement.

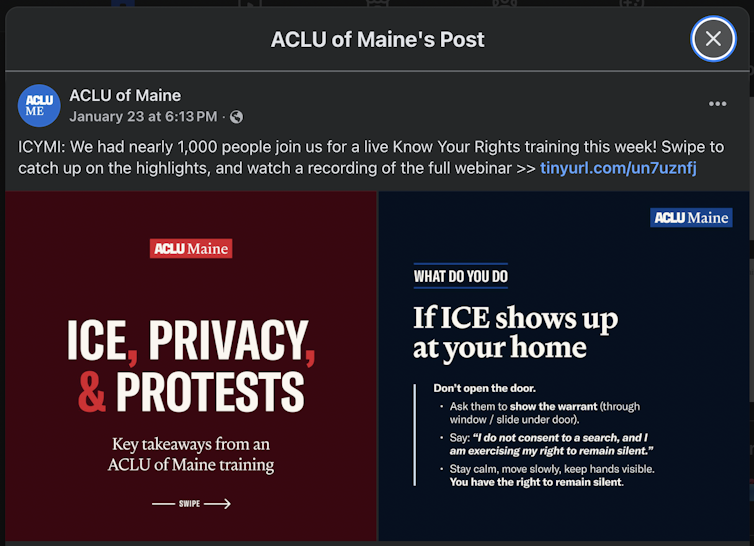

In Portland, Oregon, Community volunteers deliver food boxes of migrant families who are afraid to leave their homes. In Portland, Maine, nearly a thousand people came a virtual American Civil Liberties Union “Know Your Rights” training event. And in Minneapolis and St. Paul, the volunteers were formed networks to provide warnings using whistles and phone apps when ICE is roaming the streets.

As someone who has been studying for two decades non-violent movements in war zones, I see many parallels between these movements abroad and those that have recently been organized throughout the U.S. The communities I have studied – from Colombia to the Philippines to Syria – teach lessons about perseverance in the midst of danger that Americans have discovered innately in the past year.

These experiences show that protecting their neighbors is possible. Violence can bring feelings of fear, isolation and powerlessness, but unity can overcome fear, and nonviolence and discipline are the keys to denying powerful excuses for further escalation and harm.

But at the same time, the death of Americans Renée Good and Alex Pretti, who were part of a no violent movement and killed by immigration agents in Minneapolis, explain that taking action to protect neighbors takes courage, and the prospects are not always certain.

Here are the core lessons I learned from the people and groups I researched.

1. Organizing is the first step

Community organizing is the act of building social relationships, setting decision-making procedures, sharing information and coordinating activities.

In Colombia, I see that it is more organized communities with vibrant local councils better able to defend themselves by avoiding or resisting violence when caught between armed rebels, paramilitaries and state forces. These organizations provide reassurance to the more hesitant and encourage more people to join.

America has a strong civic culture and organizing history, dating back to the Civil Rights Movement and long before that, and Minnesota is known for strong social cohesion. It’s no wonder that many Minnesotans, as well as Chicagoans, Angelenos and other Americans are organizing to help their neighbors and pursue justice.

Make no mistake, the act of organizing itself is powerful. I find that insights from combatants in armed conflicts shed light on this. A former rebel I interviewed in Colombia quoted me the saying of Aristotle and Shakespeare: “A single swallow doesn’t make a summer” – meaning that there is safety in numbers.

A group of people by itself can change the calculus and attitude of those who have weapons and stop them. So now there are many visuals of The ICE agents left the scene when there were more members of the community.

2. Adopt non-violent strategies

Organizing also enables communities to adopt nonviolent methods for accountability and protection that do not lead to conflict.

These strategies are less political or partisan, because there is usually a consensus on promoting safety, which makes it difficult for politicians to oppose. While recently presidential approval poll and immigration policy still shows a partisan split, ICE is widely unpopular, and large majorities oppose its aggressive tactics.

Americans have adopted many of these nonviolent strategies. They set up early warning networks as communities do Democratic Republic of the Congo to guard against the attacks of the rebel group Lord’s Resistance Army.

Even with whistles or WhatsApp, such networks of defenders share information with each other to identify threats and cooperate with each other.

3. Establish safe zones

Communities in places like the Philippines have also set up safe zones or “places of peace” to publicize their desire to keep violence away from their residents. This is similar to declaration of “sanctuary cities” in the US for the immigration issue.

Communities can also use different types of pressure on armed aggressors. While protest is the most visible method, dialogue is also possible. The pressure can be taken in the form of persuasion as well as humiliation to make the trigger-happy agent think twice about what they are doing and use restraint.

In the US, defenders have shown great creativity when it comes to coercion. Grandmothers and priests are seen as influential symbols through their moral and spiritual status. The use of humor and comedy – like the protesters in the frog suits – helps reduce stress.

It may not always be this way, but reputations and concerns about accountability are important, even for bullies. That’s why ICE agents do not want to be seen to be carrying out violence. This has resulted in face masks, the confiscation of protesters’ phones and misleading statements by officials about violent encounters.

4. Finding the facts

In the “fog of war,” the powerful may try to distort the facts and mislead and disparage communities and individuals to create excuses for greater use of force.

In Colombia and Afghanistan, armed groups have falsely accused individuals of being accomplices of the enemy. Communities respond to this by do their own investigation those accused, after which the elders of the community can testify on their behalf.

In the US, Americans are recording cellphone videos and collecting community evidence to counter official lies, such as accusations of domestic terrorism – and for future efforts to maintain accountability.

Stand up for others

Finally, what is known as “together” is also important.

For example, international humanitarian staff and volunteers go into communities in places like this like ColombiaGuatemala and South Sudan to let armed groups know that outsiders are watching them and acting as unarmed bodyguards for human rights defenders.

In the US, volunteers, citizens and religious leaders use their less vulnerable social status to stand up to non-citizens who are under threat, however. positioning themselves between immigration agents and those who may be at risk. People from all over the country also send messages and travel in solidarity with cities and states where operations are conducted.

Yet there can be consequences even for those who believe themselves to be less likely to be attacked. An ICE agent on Sept. 19, 2025, shot a priest in the head with a pepper ball as he protested at the ICE detention facility in Chicago.

Acting to protect oneself, other people and communities can involve risks. But civil society has power, too, and many communities in war zones in other countries have outrun their oppressors. Americans are learning and doing what civilians in war zones around the world have been doing for decades, while also writing their own story in the process.

Oliver KaplanAssociate Professor of International Studies, University of Denver

This article was reprinted from The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com