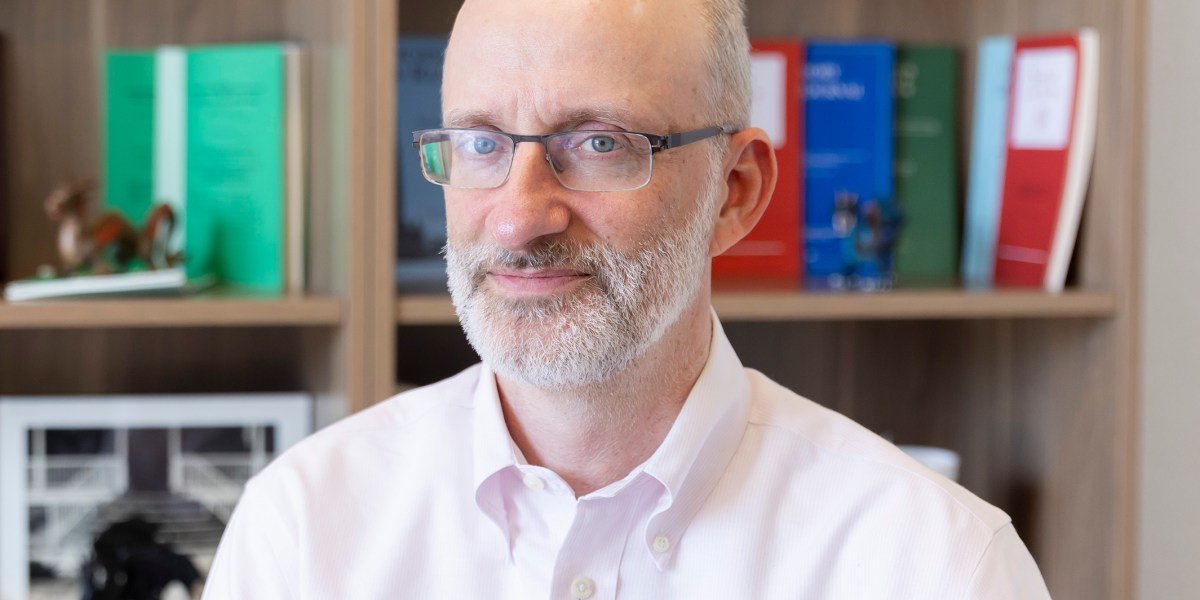

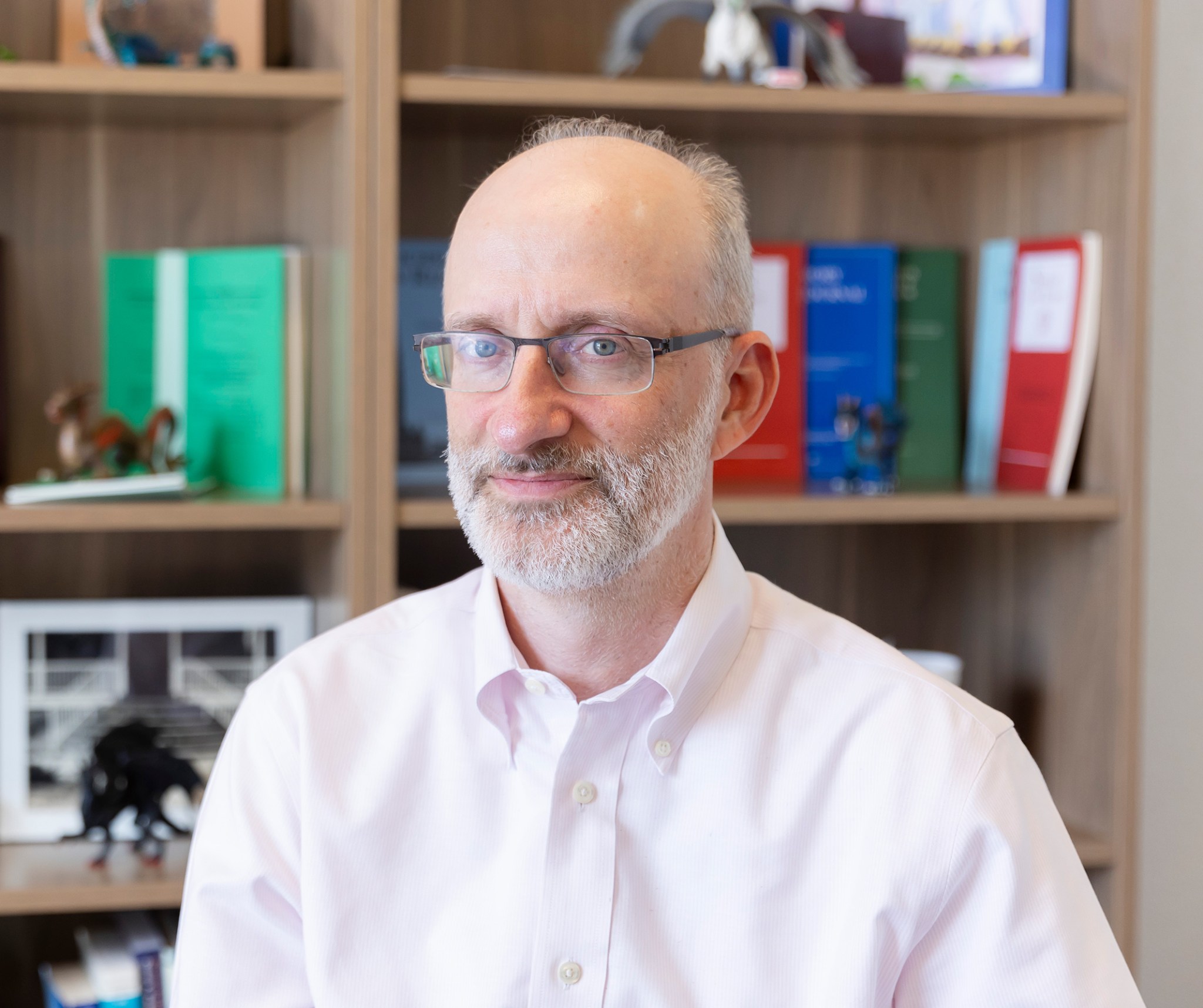

Brian Galle doesn’t want to ban billionaires. In fact, the tax law expert and key architect behind California’s controversial wealth tax proposal described himself as a “passionate capitalist” in a recent interview with Good luck. “I think capitalism is a great system that probably, you know, enriches the lives of billions of people,” he said. luck done Zooming from his office in Berkeley, where he teaches courses in tax and nonprofit law. “But I am not sure that our system is a functioning capitalist system today.

“I’m interested in how things work,” Galle added. “And now, it (capitalism) doesn’t seem to work well.” Talked to luck about his upcoming new book, How to Tax the Ultrarich, Galle said one of its central arguments is that the dominance of a small number of families leads to “bad economies” that grow more slowly and often have disruptive inflation and stagnation. (Galle’s publisher, the Roosevelt Institute, has provides a rundown of the book’s arguments.)

Galle, who recently moved to California after a decade at Georgetown Law, helped write the legislative text for the wealth tax bill introduced by Assemblymember Alex Lee to address the state’s significant budget deficit—the so-called billionaires’ tax. While previous versions of the bill have received little notice, Galle said he believes this one will garner intense scrutiny, especially from the wealthiest Californians, because it has a “very good chance of passing.”

Galle has extensive experience in wealth tax law, which has been in the past linked to a wealth tax bill from Sen. Elizabeth Warren when he was a serious candidate for president, and filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court in 2024 that cited by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. He said that should give you an idea of where his beliefs lie on the political spectrum: “The fact that he’s citing it probably tells you what six Republicans are going to think about my argument.” This is for Moore v. United Stateswhich supports an international tax provision while clearly avoiding a broad ruling on whether “unrealized” gains can be taxed as income, which just happens to be at the heart of wealth tax and what billionaires do. “So maybe,” Galle added, “the Supreme Court will say you can only tax people when they sell.”

The question of ‘when is the tax’ and the many loopholes of the billionaire

This is the core problem, however, Galle said: The American tax system allows the rich to choose when they pay taxes, a choice that they often delay indefinitely. Citing research by economist Emmanuel Saez, Galle noted that billionaires pay an all-in tax rate that is 20% lower than the median American household. While the American tax code may look progressive on paper, he argues, it is not very practical, as the ultra-rich can choose whether to sell assets and realize capital gains, which trigger taxes. Until then, they can, under a practice known as “buy-borrow-die,” kept borrowing against their assets to fund their lifestyles. “I don’t know about you,” Galle said, “but when I go into my Fidelity account, I have a little button that I can click that says, ‘Do you want to borrow against your savings?’ I’m sure it’s easier for billionaires.

Critics of the California proposal, including a tech billionaire Palmer Luckeyargued that a wealth tax would force them to liquidate businesses and burn workers to pay the bill. Galle rejected this, saying, “The idea that they have to sell a significant part of their assets to pay a 1% annual tax is just nonsense.” Galle also rejected the argument that wealth taxes are destined to fail because they have been scrapped in many countries such as France, pointing to successful, sustained models in Switzerland and Spain that close loopholes for private businesses.

Why are so many wealth taxes being rolled back around the world, then? According to Galle, it’s a combination of factors, but one of them is that over time, “billionaires learn better and better, and their lawyers learn how to find all the loopholes to really take advantage of this kind of optionality: their ability to choose when to pay taxes.” Galle allows that different billionaires have different assets and some are difficult to value (in the world of private art collections, as luck reportssome investors develop esoteric tastes, such as collecting dinosaur bones), but Galle said that these obstacles can be “solved” in the form of formulas and assessments.

Kent Smettersa Wharton professor and faculty director of the Penn Wharton Budget Model, said luck that he agreed that these issues need to be resolved and that the buy-borrow-die model “may be a legitimate issue,” adding that it is “not really based on tax principles or equal tax principles.”

Smetters, who has said before luck that his own research shows that taxing billionaires doesn’t bring in as much revenue as is commonly believed, granted it’s a moral issue for many, and that makes sense. “My feeling is that (wealth tax advocates) still believe in it just because of this principle. And it’s true that sometimes the really rich billionaires, they manage their tax “by borrowing against their wealth and not realizing capital gains while they save. The key is dealing with what’s called a “step-up in cost basis,” where an heir steps up to the fair market value of their parent’s wealth at the time of death. “That’s the tail that’s wagging the dog here,” Smetters says, and dismisses that as potentially detrimental to some common tax planning strategies of the super-rich: “Maybe you can satisfy some of the concerns that people have about this principle of fairness.”

How to fix it with ‘FAST’

The main focus of Galle’s book, of course, is the “how” to make this actually happen. California’s billionaires tax is a one-off, for a state with a $100 billion funding gap, he explained. He (and his co-authors) envision a federal-level solution, explained in detail in his upcoming book, called “FAST.”

Under the FAST plan, the government will wait until wealthy individuals sell their assets to tax them, which is likely to follow Supreme Court requirements. However, the government will charge an interest rate that retroactively eliminates the financial benefit of delaying the sale. By charging an “economically appropriate interest rate,” Galle argued, the plan removes the incentive to hoard assets to minimize tax bills, encouraging the wealthy to sell quickly (this also explains the “FAST” title). This measure only applies to the highest level of wealth holders, likely those with more than $30 million in assets.

FAST also resolved the cost basis step-up by replacing the estate and gift tax system with an extra tax bracket for inherited property, “in effect moving to an inheritance tax and carryover basis at death, but again with additional interest charges for taxpayers who delay the sale.” It solves two problems in one fell swoop, he explained.

Galle acknowledged that the Supreme Court signaled 2024 Moore ruled that it would not allow the tax of unrealized gains, and he explained that his proposal was designed in accordance with what is likely to be legal. But he insists that these proposals should be seen not as a way to punish success, but as an important continuation of a capitalist system that is currently skewed by “disproportionate billionaire power.” He argues that functioning capitalism requires a “fair, practical tax system” rather than the current setup, which allows the wealthiest to opt out of paying their share. While he admits there are no “magic wands,” Galle insists the current tax code exacerbates economic inequality, and increased growth is essential to restoring a healthy economy.