Last year, physicists created a time crystal—an atomic arrangement that repeats motion patterns—see in the eye. But the latest research on this quantum eccentricity may represent more than a few steps forward.

This time crystal, described by a new Physical Review Letters paper, big enough to hold in your hand, and it floats. Discovered by a group of physicists at New York University (NYU), the new type of time crystal consists of styrofoam-like beads that levitate on a sound cushion while exchanging sound waves.

If that’s not surprising enough, the time crystal does so by violating Newtonian physics—and the team believes that gives the new crystal both academic and practical significance.

“It was a discovery in the truest sense,” David G. Grierthe senior author of the study and a physicist at NYU, told Gizmodo. “Perhaps the most amazing thing is that such rich and interesting behavior emerged from such a simple system.”

What are time crystals?

In 2012, Nobel laureate Frank Wilczek up an idea for an impossible crystal that breaks the symmetry rules of physics. Generally, solid crystals maintain a continuous lattice of their individual components. Time crystals, however, do the exact opposite, with the individual atoms within them changing positions over time in a relatively fixed pattern.

In the past decade or so, physicists have been able to find different versions of Wilczek’s vision. But these instances often represent short-term, microscopic time crystals with little practical implication. Just last year a team at the University of Colorado Boulder proposed a crystal design of time that we can actually see.

Styrofoam has found a new quirk

The newly discovered time crystal may represent many advances in the practical relevance of time crystals. For one, the bead in the experiment was expanded polystyrene—the same material used in styrofoam packaging.

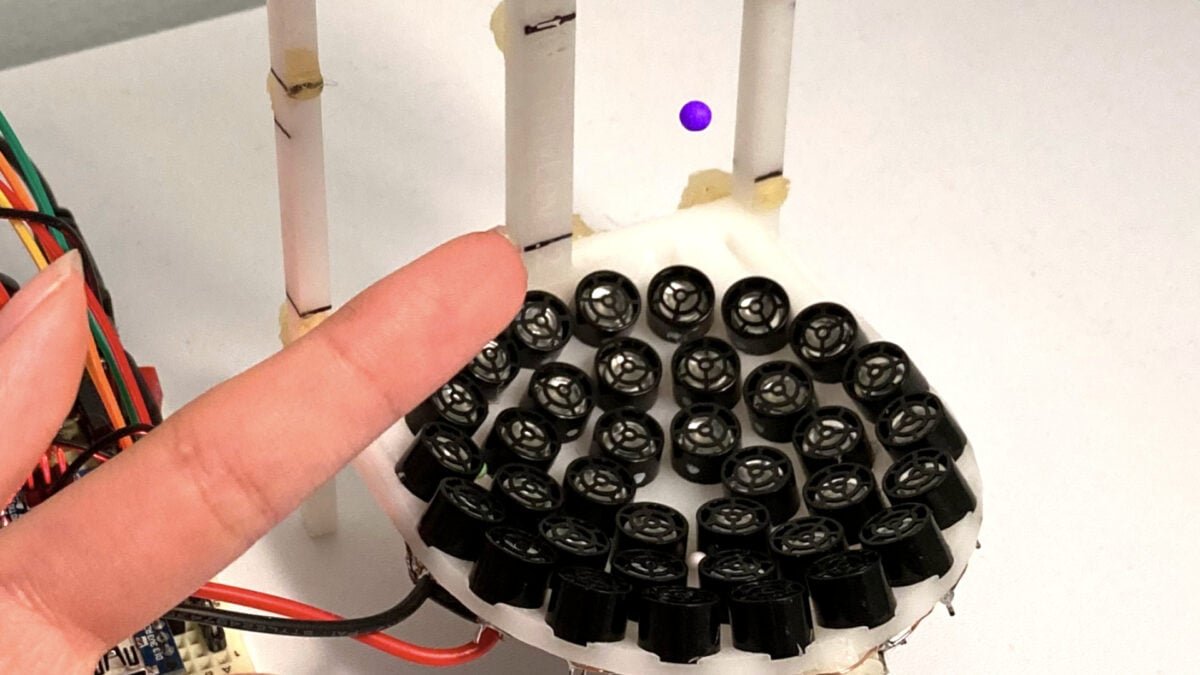

The team turned this common material into a time crystal by suspending styrofoam beads in sound waves. On its own, the bead floats without motion, but things start to change once several beads collide.

In this system, each bead scatters its own portion of sound waves. That contributes to an overall system of “non-equilibrium interactions” that actually allow particles to harvest and impart energy from sound waves, Grier explained. “The important point is that time crystals choose their own frequency without being told what to do by any outside force.”

The simplest of all?

Furthermore, these interactions are not bound by Newton’s third law of motion, which dictates that two bodies pressing against each other must exert the same amount of force in opposite directions.

“Imagine two ferries of different sizes heading to a port,” Mia Morrell, the study’s lead author and a graduate student at NYU, said at a university. statement. “Each creates water waves that push the other around—but to different degrees, depending on their size.”

According to Grier, the extreme simplicity of this time crystal setup may have made it a “hydrogen atom” for this phenomenon – highlighting its potential in other contexts, such as “the neural pacemakers of our hearts in the cyclical trends of financial markets.”

“We hope that the study of a small model will provide access to the deepest insights into the spontaneous emergence of clocks in more general and more complex manifestations,” he added.