The Sam Altman-chaired Helion Energy fusion power developer announced a new milestone on February 13 reaching a record plasma temperature of 150 million degrees Celsius—10 times that of the sun’s core—as part of its more ambitious goal to bring power to the grid in Washington state by 2028.

Fusion energy startup developers—the the so-called star power in a jar—racing to prove their technologies and bring clean, unlimited electricity to the grid to meet the power needs of the AI boom. While Helion has the most aggressive timeline for the first commercial power-under contract for Microsoft data centers—skeptics have questioned Helion’s start date, the technology’s unique approach against competitors, and the lack of scientific updates to date.

“While interstitial milestones are very important to show that the technology works and you can get regulatory approval, at the end of the day, it’s about deploying power plants at scale to support growing electricity demand,” said Helion cofounder and CEO David Kirtley. luck.

“We are on schedule to have the first electrons on the grid in 2028. This is an aggressive milestone. It will be difficult,” said Kirtley. “Part of that is the progressive restoration and parallel development now in Malaga, Washington.”

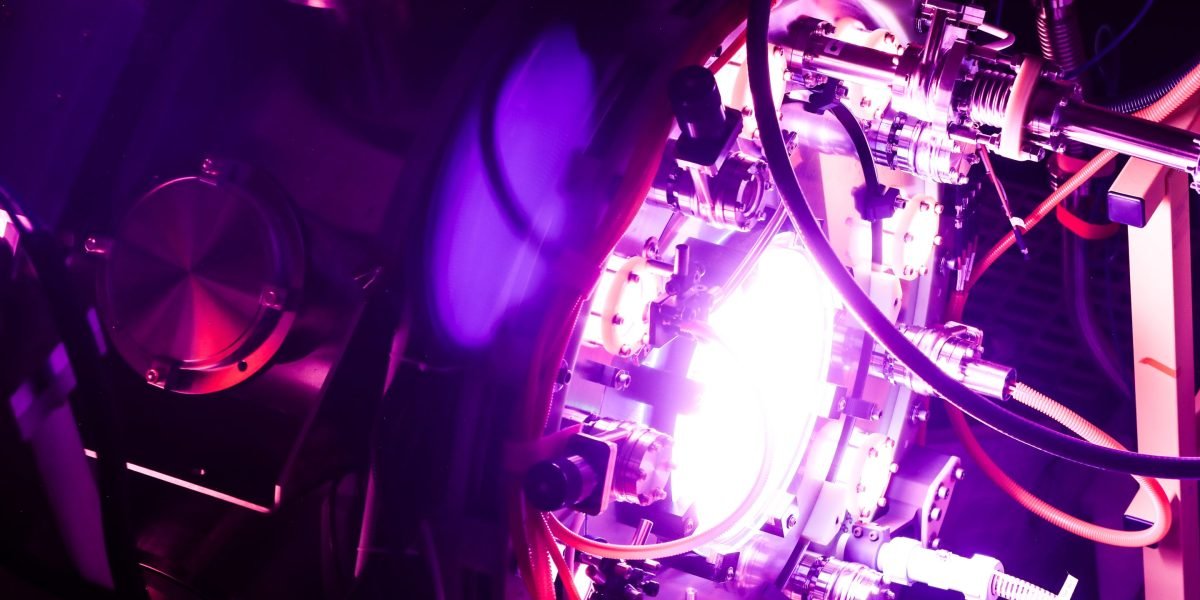

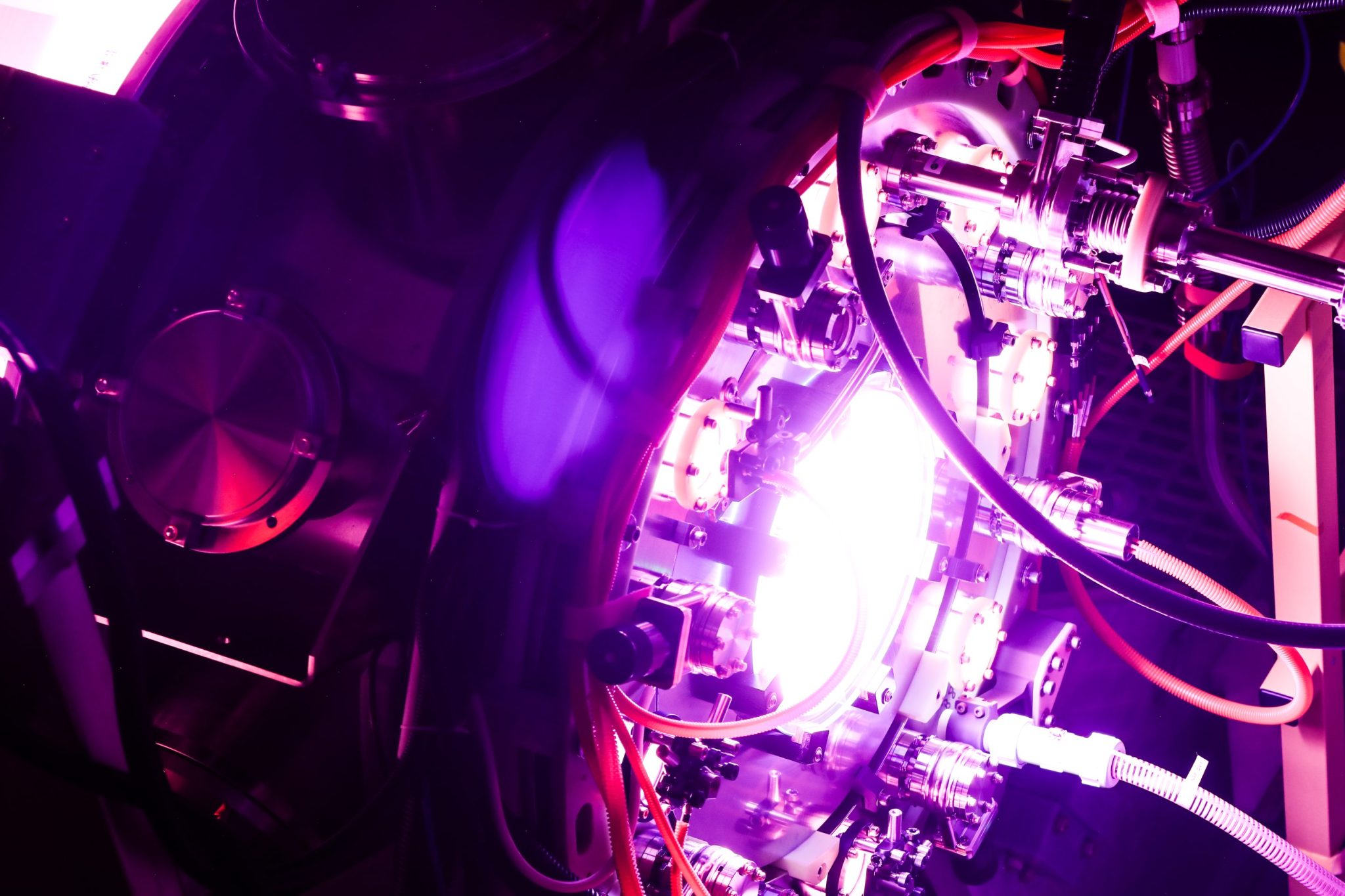

While the success of plasma heat is set in the seventh generation Helion prototype, Polarisin suburban Seattle, Helion is already building its 50-megawatt commercial power plant, Orion, 130 miles away in Malaga—near Microsoft’s growing data center campus. Helion has yet to assemble the fusion reactor, which requires further engineering and design finetuning.

Developing multiple projects in parallel—including an assembly line manufacturing system—was key to Helion’s rapid pace and success, Kirtley said. “This is how we’ve been able to build seven generations of fusion systems and do it faster than anyone else in fusion. The core philosophy of how we operate is to rapidly build, test, iterate, and rebuild.”

While traditional nuclear fission energy creates power by splitting atoms, fusion uses heat to create energy by fusing them. In its simplest form, it fuses the hydrogen found in water into an extremely hot, electrically charged state known as plasma to create helium—the same process that powers the sun. When executed correctly, the process triggers endless reactions to produce energy for electricity. But stars rely on intense gravitational pressure to force them to merge. Here on Earth, creating and containing the pressure needed to force the reaction in a consistent, controlled manner remains an engineering challenge.

And, since fusion reactors are much smaller than stars, they must produce heat at much hotter concentrations than stars. The sun is about 15 million degrees Celsius at its core, or 27 million F.

About 100 million degrees Celsius is considered the minimum threshold for continuous commercial fusion power, hence the enthusiasm for the new milestone.

Helion was founded in 2013 and Altman became chairman and a major financial backer in 2015 — before he founded OpenAI. Altman also became chairman of the nuclear fission, small modular reactor (SMR) startup Oklo that same year. Other key Helion investors include LinkedIn cofounder Reid Hoffman and Facebook cofounder and current Asana CEO Dustin Moskovitz. Kirtley said Altman’s role is to focus on the long-term vision.

“One question I get from Sam is, ‘How can we move faster?’” Kirtley said. “We’re on an aggressive timeframe. ‘How can we move faster than that? How can we quickly leverage the power of scale?'”

Unique fusion method

Kirtley previously worked at the NASA-backed MSNW on fusion-driven rocket technologies. He built Helion with a dual focus on fusion power and fusion propulsion. The propulsion work helped Helion change its unique power approach, he said.

“One thing you learn about working in space and building systems to fly in space is that you don’t waste anything. Every ounce of weight is critical; every watt of power is critical,” Kirtley said. “You have to be very efficient everywhere and all the time. If you take the same approach and apply it to fusion, all the physics requirements are reduced.”

Most fusion technologies, as well as nuclear fission, are based on generating heat into steam turbines, which generate electricity. Helion’s technology captures electricity during the fusion process—no need for turbines.

“That’s really the fundamental difference that we believe allows us to move faster than other people,” Kirtley said. “That reduces the scale of the fusion system. Reduces how hard it is to do.”

Helion’s fusion fuel combines deuterium from water with tritium. Helion was the first company licensed to use radioactive tritium as a fusion source. But the ultimate goal is to use deuterium and helium-3, which Helion aims to create by fusing the same deuterium atoms. Helium-3 allows the process to generate more electricity with less heat.

It makes sense to Helion Fusion’s main competition is Nvidia and Bill Gates-backed Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), which has deeper pockets but takes a more conservative approach. The Commonwealth relies on the most traditional fusion technology — relatively new for an industry that has never generated electricity on the grid.

CFS is currently building its SPARC fusion prototype that will come online next year. But that will not provide power to the grid. If SPARC succeeds, CFS’s first commercial fusion plant, ARC, is scheduled to be built and come online in the early 2030s outside of Richmond, Virginia. If all goes according to plan, the 400-megawatt plant—more powerful than Helion’s Orion—will produce enough electricity to serve about 300,000 homes.

The CFS relies on a so-called tokamak design—short for toroidal chamber magnetic—that relies on its powerful magnets. The technology basically involves a large, donut-shaped machine that traps plasma in a high-temperature, superconducting magnetic field. But the process produces heat, not electricity.

The smaller, but faster Helion method uses magneto-inertial fusion. In theory, plasmas collide in the fusion chamber and are compressed by magnets around the machine. That heats the plasma, promotes fusion reactions and results in a change in the plasma’s magnetic field. This change interacts with the magnets, increases their magnetic field, and starts to flow new electricity through the coils.

The reason is that it is complicated and there is no guarantee of success for any of the fusion developers. But Kirtley said he’s confident that fusion power will make a significant dent in the US power grid within the next decade and continue to grow from there.

“If all we do is build the world’s first fusion power plant, as a company, we have failed,” Kirtley said. “Our goal is to deploy clean and safe baseload power in the world. That means building technologies in a way that is scalable, mass producible, and must be low-cost so that the customer wants it.”