It’s only 8 o’clock One day last April, an office manager named Amani sent an encouraging message to his colleagues and subordinates. “Every day brings a new opportunity—a chance to connect, inspire, and make a difference,” he wrote in his 500-word post to an office-wide WhatsApp group. “Tell the next customer like you brought them something of value—because you are.”

Amani does not rally a typical corporate sales team. He and his subordinates work within a “roast pork” compound, a criminal operation set up to execute scams—promise romance and wealth from crypto investments—which FOR the most part defrauding victims out of hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars at a time.

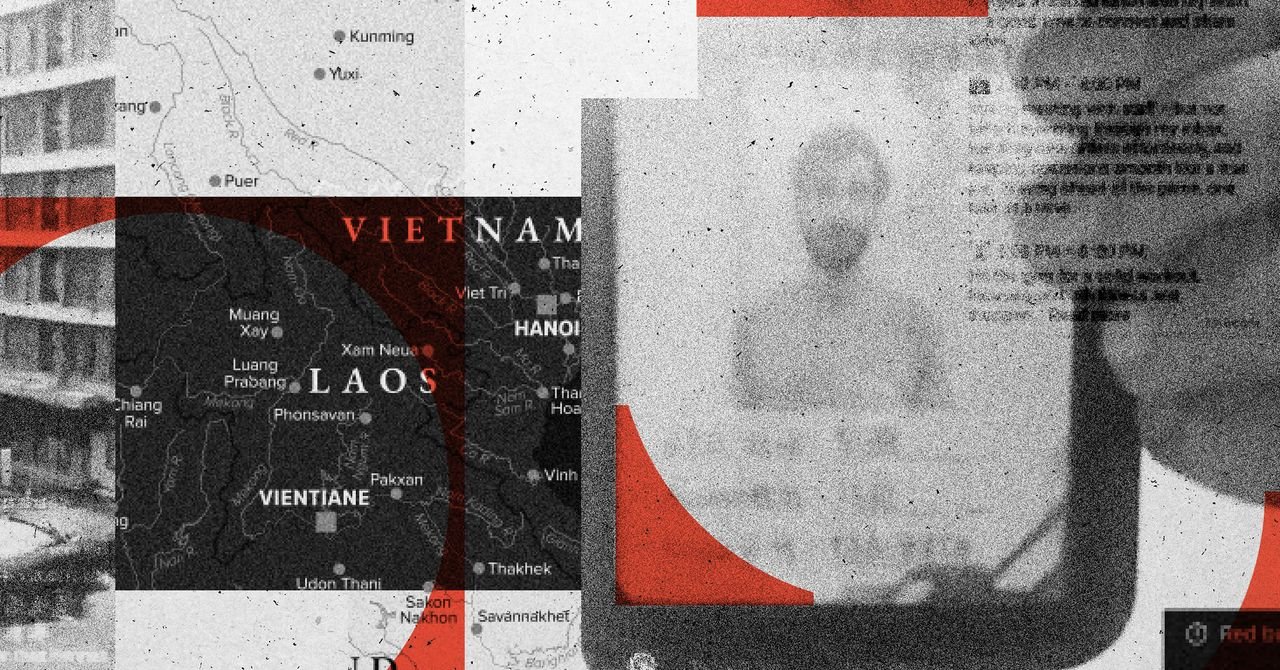

The workers addressed by Amani were eight hours into their 15-hour night shift in a high-rise building in the Golden Triangle special economic zone in Northern Laos. Like their marks, most of them were victims, too: forced laborers trapped in the compound, bound by debt without passports. They struggle to meet the scam’s income quotas to avoid fines that will deepen their debt. Anyone who broke the rules or tried to escape faced harsher consequences: beatings, torture, even death.

The strange reality of day-to-day life in a Southeast Asian scam compound—the tactics, the tone, the mix of brutality and spirited corporate prattle—is revealed at an unprecedented level of resolution in a leak of documents to WIRED from a whistleblower inside one such massive fraud operation. The facility, known as the Boshang compound, is one of dozens of scam operations across Southeast Asia that have enslaved hundreds of thousands of people. Usually attracted from the poorest regions of Asia and Africa with fake job offers, these conscripts have become the engine of the most profitable form of cybercrime in the world, forced to steal tens of billions of dollars.

In June, one of the forced laborers, an Indian named Mohammad Muzahir, contacted WIRED while he was still a captive inside the scam compound that had trapped him. In the weeks that followed, Muzahir, who initially identified himself as “Red Bull,” shared more information with WIRED about the scam operation. His leaks include internal documents, scam scripts, training guides, operational flowcharts, and photos and videos from inside the compound.

Of all Muzahir’s leaks, the most revealing was a collection of screen recordings in which he scrolled through three months’ worth of internal chats in the compound’s WhatsApp group. Those videos, which WIRED converted into 4,200 pages of screenshots, capture hour-by-hour conversations between workers at the compound and their employers—and the appalling workplace culture of a pig-slaughtering organization.

“It’s a slave colony trying to pretend it’s a company,” said Erin West, a former Santa Clara County, California, prosecutor who heads an anti-scam organization called Operation Shamrock and who reviewed chat logs obtained by WIRED. Another researcher who examined the leaked chat logs, Jacob Sims of Harvard University’s Asia Center, also commented on their “Orwellian veneer of legitimacy.”

“It’s terrible, because it’s manipulation and coercion,” says Sims, who studies scam compounds in Southeast Asia. “Putting the two things together motivates people. And this is one of the main reasons why these compounds are so useful. “

In another chat message, sent within hours of Amani’s saccharine pep talk, a higher-level boss weighed in: “Don’t go against company rules and regulations,” he wrote. “Otherwise, you wouldn’t survive here.” The staff responded with 26 emoji reactions, all thumbs-ups and salutes.

Fined Into Slavery

In general, according in WIRED’s analysis of the group’s chat, more than 30 of the compound’s workers successfully defrauded at least one victim in the 11 weeks of records available, totaling $2.2 million in stolen funds. Yet chat bosses often express their disappointment with the group’s performance, chastise staff for lack of effort, and hand out fine after fine.

Rather than outright imprisonment, the compound relied on a system of indentured servitude and debt to control its workers. As Muzahir described, he was paid a base salary of 3,500 Chinese yuan a month (about $500), which theoretically required 75 hours a week of night shifts including meal breaks. Although his passport was taken from him, he was told that if he paid his “contract” with a fee of $5,400, it would be returned to him and he would be allowed to leave.