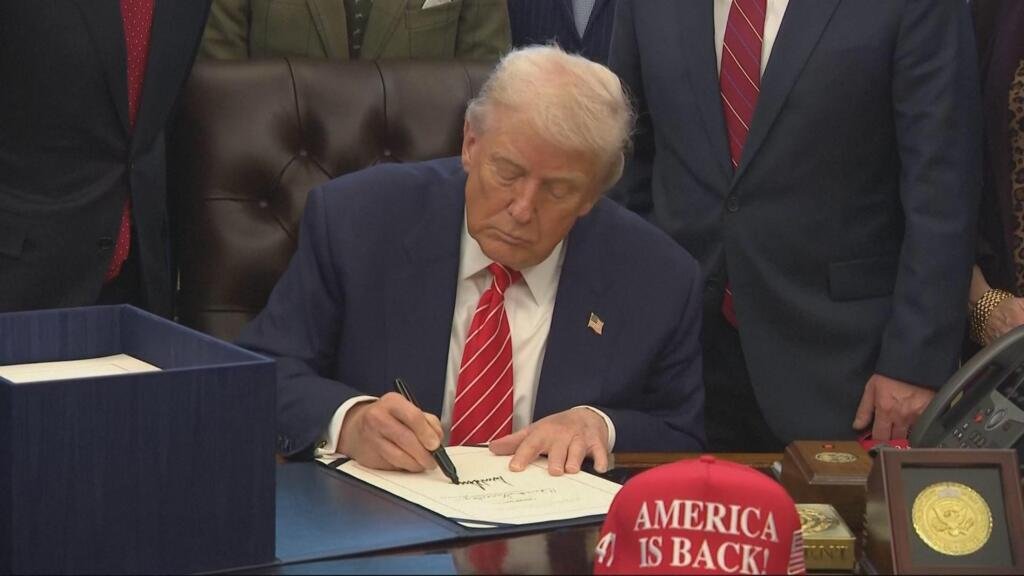

Palantir’s fourth-quarter earnings call turned into a geopolitical broadside as CEO Alexander Karp blasted Canada and much of Europe for falling in the artificial intelligence race, casting the global economy as a looming conflict between “AI haves” and “have-nots.”

Speaking after Palantir reported 70% year-over-year revenue growth to $1.407 billion in the fourth quarter and a Rule of 40 score of 127, Karp argues that the company’s performance reveals a growing gap between countries and institutions that are ready to overhaul themselves around advanced AI software and those that will erode margins.

Noting that Palantir’s US business grew 93% year-over-year in the fourth quarter, with America now accounting for 77% of total revenue, Karp asked hypothetically, “what do bombastic numbers like this mean?” It’s actually bad news that Palantir is “doing things that no other company has ever done,” he argued, because it raises another question: “it’s obviously of importance for the world. And what does that mean for the world?”

Karp as Davos Man 2.0

sounding rhetoric from the Trump administration presented at the recent World Economic Forum in Davos (where Karp was a speaker), the Palantir CEO offered a withering critique of companies that have failed to adopt AI. “We also see, unfortunately, that there is a real reluctance to adopt these types of Western products outside of America, and the two places that lead here are China and America,” he said. “What we’re seeing in America is a wide disparity. And so the non-adopters, the non-adopters, are hoping for a catch-up function.” Good luck, he said, noting that Palantir’s earnings are a “breakout function” that means “the value approach is clearly irrelevant.”

The value that Palantir creates is “so large and so disproportionate that you can create a company that seems to explode in terms of growth and quality of growth.” He then named names, saying Palantir has seen adoption, sometimes wide, of advanced AI platforms in parts of the Middle East and China, but “lack of adoption in Canada, Northern Europe, and Europe in general.” Just look at France, he said, one of the countries with “the clearest idea of the problem.” France has no alternative to solve this adoption problem and is forced to continue signing new deals with Palantir. In December 2025, until that point, France renewed the three-year contract with the French intelligence services.

“One of the things you see in Northern Europe, Canada, and other places is a real pressure to move left and right politically, very far,” Karp said. “Because the way you deal with it is when you don’t have an answer to a question, you create ideologies that don’t make sense, and you try to implement them.”

To be sure, Karp’s framing ignores that Palantir itself has chosen to focus on US capacity and “doesn’t have the bandwidth” for more complex international work. It also negates legitimate reasons for slower or more selective adoption: Regulatory regimes in Europe and Canada place a higher emphasis on privacy, civil liberties, and vendor diversity, with many governments preferring sovereign or local solutions to critical infrastructure. It also treats Palantir’s success in an unusually favorable defense-centric market in the US as if it were universal proof that countries like Canada and those in Europe failed AI simply because they didn’t buy its platform at scale. Different jurisdictions have the right to pursue AI on their own timelines, with their own safeguards and mix of vendors.

Wall Street analysts, as they are prone to do in a hot stock, sided with Karp’s version of events. Bank of America Research, for example, argues that Palantir’s explosive earnings constitute a “warning to slow down adapters” in AI: “the clock is ticking.” Exponential growth is demonstrated here in line with Palantir’s deliberate actions on how to go-to-market, develop products, and become an enabler of AI decision-making, BofA wrote. If companies really want to become “AI companies,” analysts added, they need to deliver real results. Granting that the market relationship with AI companies “continues to change,” BofA sees this set of results cementing Palantir’s place “as one that can survive and thrive in the chaos.”

The haves and the have-nots

Inside the companies, Karp and President Shyam Sankar describe the same divide between AI “haves” and “have-nots.” Chief Revenue Officer Ryan Taylor said some customers are now signing initial deals of $80 million to $96 million within months and rapidly expanding use, citing examples of utility and energy clients whose annual contract value quadrupled or quintupled by 2025. Taylor framed the customers as “native AI businesses” that are starting with large commitments and quickly measured in hundreds of thousands of use cases.

“Our customers aren’t tentatively testing AI; they’re committing to it at scale,” Taylor said, adding that Palantir’s top 20 customers now generate an average of $94 million each in trailing 12-month revenue, up 45% year-over-year. Karp argues that these companies are “defining the future of their industries,” while those still dabbling in pilots — the “AI that doesn’t exist” — are “fighting for survival right now.”

BofA noted how embedded Palantir is in the corporate space, with an ever-expanding list of mentions on earnings calls, with 17 unique mentions this quarter up from seven a year ago, and a new high of 38 total mentions, up from 25 last quarter.

Karp’s comments come as Palantir is confident in its role as a key supplier of AI-enabled systems to the US government and defense sector. The company touted a US Navy contract worth up to $448 million to transform the shipbuilding supply chain and described its “Ship OS” and “warp speed” industrial tools as part of a broader push to industrialize American defense manufacturing. Sankar said usage of Palantir’s Maven defense AI platform is at “all-time highs,” with the system supporting simultaneous real-world military events and being pushed into more combatant commands and edge environments.

For now, Palantir’s capacity constraints and rising US demand give Karp little incentive to ruffle feathers overseas. He said the company “doesn’t have the bandwidth to do anything difficult outside of America” and questioned whether European procurement systems are sufficiently “carrying the load” to buy “the best product” if it means favoring US sellers over domestic champions.

At times, Karp almost feels sorry for his European competition. “Believing that you can go and build companies without this much risk,” Karp said of orchestrated, production-level AI systems. “How do you produce even half of this level Can be a real question for technology companies and a real question for countries. Can we produce companies that produce what we produce in a quarter of a year?”