Science Corporation, the brain-computer interface startup founded in 2021 by the former Unfathomable president Max Hodak, launched a new division of the company with the goal of extending the life of human organs. And no, not brain.

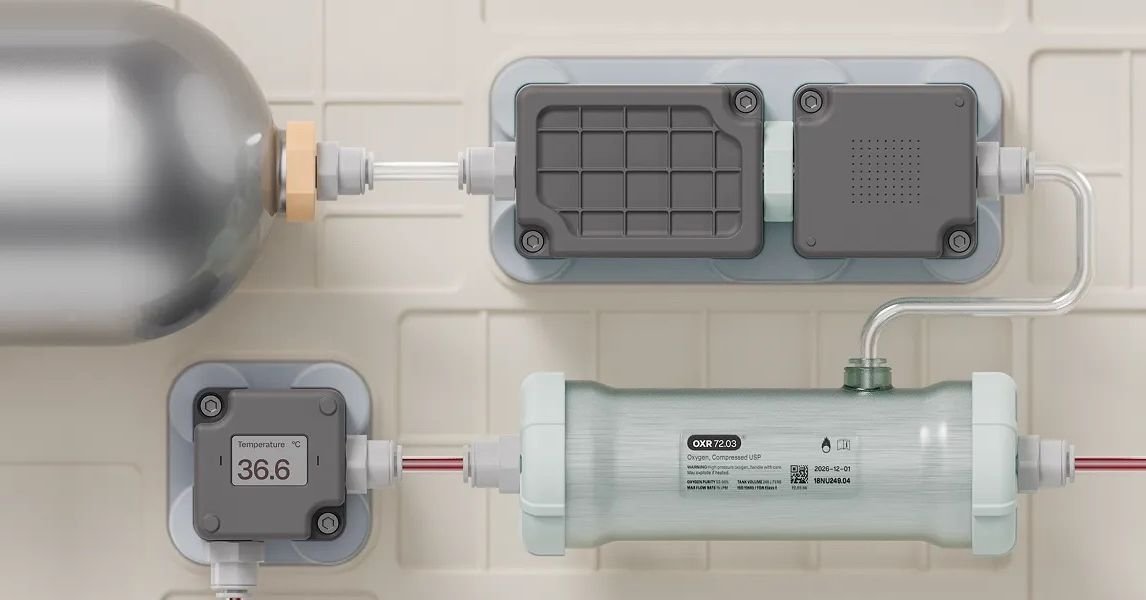

Alameda, California-based Science aims to improve current perfusion systems that continuously circulate blood through vital organs when they can no longer function on their own. The technology is used to preserve organs for transplant and as a measure to support the life of patients when the heart and lungs stop working, but it is clunky and expensive. Science wants to create a smaller, more portable system that can provide long-term support.

Until now, the focus of Science has been on neural interfaces and vision restoration. The company is working on a “biohybrid” interface that uses living neurons instead of wires to connect to the brain. More immediately, it is looking to commercialize its retinal implant, which has been successful restored some vision in patients with advanced macular degeneration, allowing them to read letters, numbers, and words. Science acquired the implant in 2024 from the French startup Pixium Vision, which faced bankruptcy, and jumped ahead of Elon Musk’s Neuralink to develop an implant for vision loss.

“In some sense, they’re both longevity technologies, and that’s the purpose of neural interfaces and this,” Hodak said of organ perfusion.

Hodak founded Neuralink with Musk and others in 2016 but left in 2021 to start Science and serve as CEO. Since its founding, Science has raised nearly $290 million, according to venture capital database Pitchbook.

Hodak was inspired to work on organ preservation after reading about case of a 17-year-old boy in Boston whose lungs were failing due to cystic fibrosis. He was sustained by a type of perfusion called extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, while awaiting a transplant. But after two months on the waiting list, he developed a complication that made him ineligible for a transplant. His doctors and parents faced the ethical dilemma of keeping him alive on ECMO, which was meant to serve as a short-term bridge. Eventually, the machine’s oxygenator began to fail and doctors chose not to replace it. Soon, the boy lost consciousness and died.

Used during the Covid-19 pandemic for patients whose lungs have failed, ECMO machines are expensive and resource-intensive. They cost thousands of dollars a day to run, and patients are tied to them in the hospital. Consisting of a large circuit of tubes that must be wheeled on a bedside cart, it requires constant monitoring and frequent manual adjustments. Because of their high cost, not all hospitals have them.