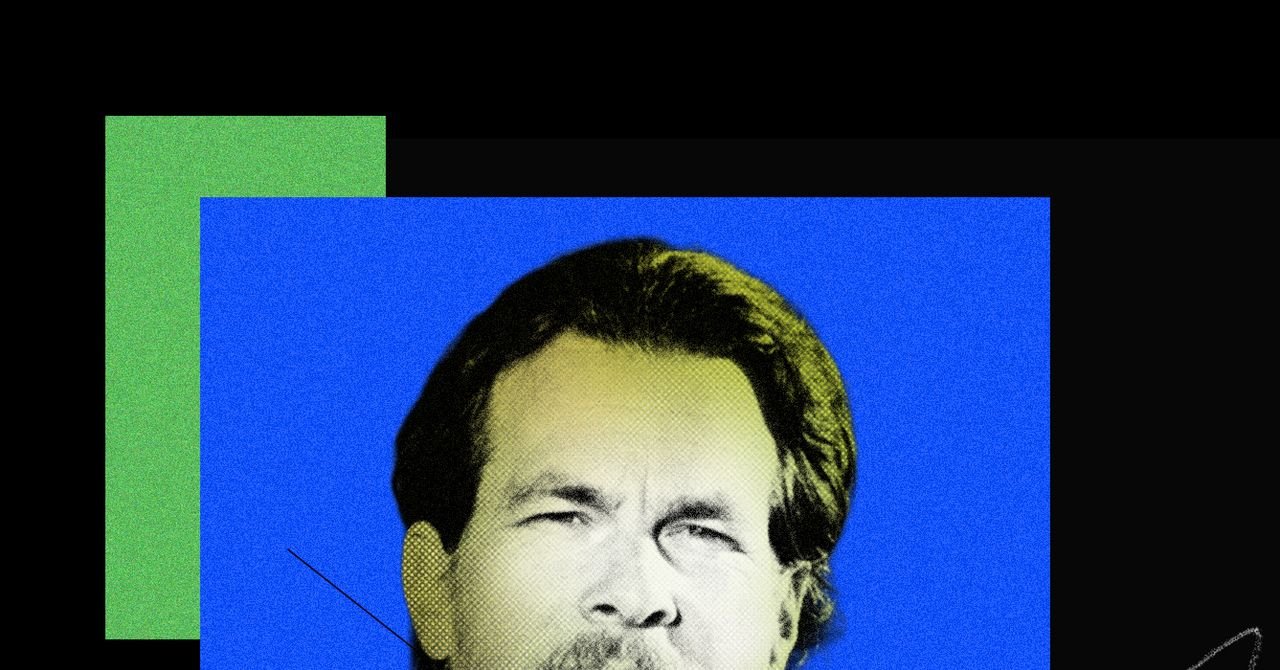

Nuclear fusion creates images of large reactors or banks of many large lasers. Avalanche co-founder and CEO Robin Langtry thinks smaller is better.

Over the past few years, Langtry and his colleagues at Avalanche working on what is a desktop version of nuclear fusion. “We use small size to learn quickly and iterate quickly,” Langtry told TechCrunch.

Fusion power promises to provide the world with plenty of clean heat and electricity, if researchers and engineers can solve some daunting challenges. At its core, fusion power seeks to harness the power of the Sun. To do that, fusion starters must figure out how to heat and compress the plasma long enough for the atoms inside the mix to fuse, releasing energy in the process.

Fusion is a notoriously unforgiving industry. The physics are challenging, the materials science is advancing, and the power requirements can be enormous. Parts must be machined with precision, and the scale is often too large to avoid rapid fire experimentation.

Some companies like Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) use large magnets to feed plasma into a doughnut-like tokamak, others compress fuel pellets by shooting them with powerful lasers. Avalanche, however, uses electricity at extremely high voltage to get plasma particles into an orbit around an electrode. (It also uses some magnets to keep things in order, though they’re not as powerful as the tokamak.) As the orbit tightens and the plasmas accelerate, the particles begin to smash into each other and mix.

The approach won over some investors. Avalanche recently raised $29 million in an investment round led by RA Capital Management with participation from 8090 Ventures, Congruent Ventures, Founders Fund, Lowercarbon Capital, Overlay Capital, and Toyota Ventures. To date, the company has raised $80 million from investors, a a relatively small amount in the fusion world. Some companies have raised several hundred to several billion dollars.

Space-based inspiration

Langtry’s time at Jeff Bezos-backed space tech company Blue Origin influenced how Avalanche tackled the problem.

Techcrunch event

Boston, MA

|

June 23, 2026

“We know that using this kind of ‘new space’ approach at SpaceX is that you can come back quickly, you can learn quickly, and you can solve some of these challenges.” said Langtry, who works with co-founder Brian Riordan at Blue Origin.

Being small allows the Avalanche to be fast. The company used to be test changes to its tools “sometimes twice a week,” something that is challenging and expensive for a large tool.

Currently, the Avalanche reactor is only nine centimeters in diameter, although Langtry said the new version will grow to 25 centimeters and is expected to produce about 1 megawatt. That, he says, “gives us a significant burst of confinement time, and that’s how we get plasmas that have a chance of being Q>1.” (In fusion, Q refers to the ratio of power in to power out. If it’s greater than one, the fusion device is said to be past the breakeven point.)

The experiments will be conducted at Avalanche’s FusionWERX, a commercial test facility that the company also leases to competitors. In 2027, the site will be licensed to handle tritium, an isotope of hydrogen used as fuel and essential to many plans to start fusion to generate power for the grid.

Langtry wouldn’t commit to a date for when he expects Avalanche to produce more power than its fusion devices use, a key industry milestone. But he thinks the company is on the same timeline as competitors like CFS and the Sam Altman-backed Helion. “I think there are a lot of exciting things that will happen in fusion in 2027 to 2029,” he said.