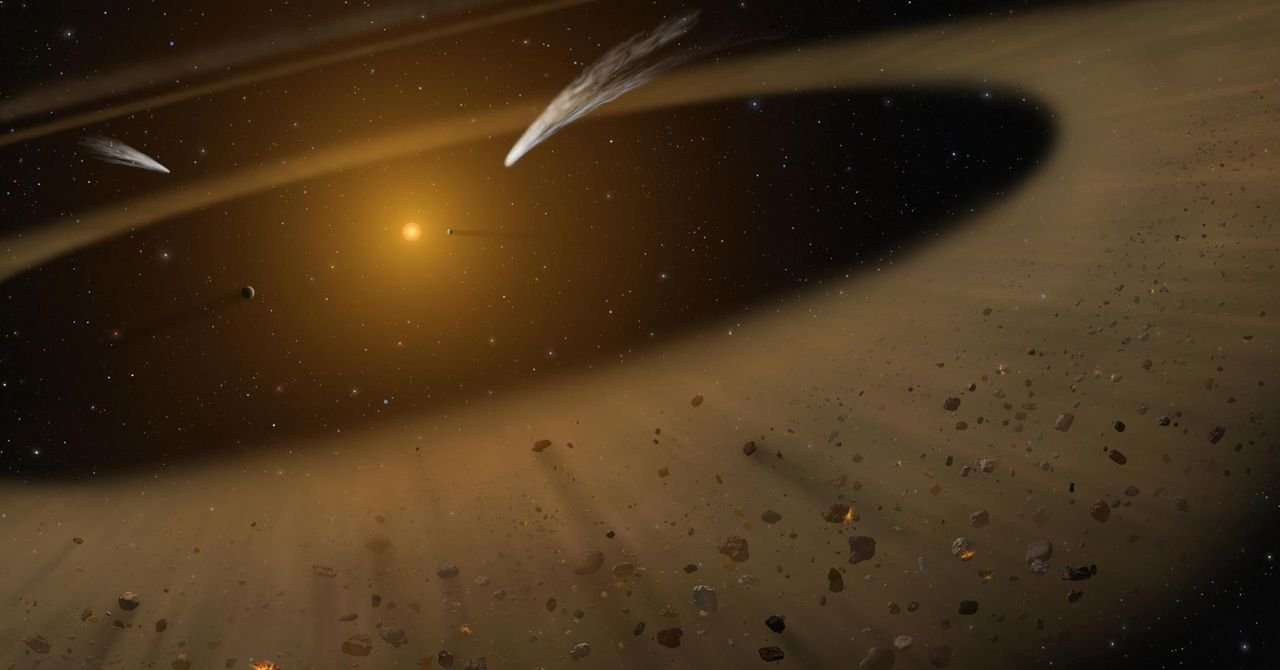

Apart from Neptune’s orbit lies a vast ring of ancient relics, dynamic enigmas, and possibly a hidden planet—or two.

the Kuiper Belta region of icy debris some 30 to 50 times farther from the sun than Earth—and perhaps even farther, though no one knows—has been shrouded in mystery since it was first spotted in the 1990s.

Over the past 30 years, astronomers have identified about 4,000 Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs), including a small dwarf world, icy comets, and planetary remnants. But that number is expected to increase tenfold in the coming years as observations from more advanced telescopes come in. Other follow-up observatories, such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), will also help bring the belt into focus.

“Beyond Neptune, we have a census of what’s in the solar system, but it’s a patchwork of surveys, and it leaves a lot of room for things that might be out there that aren’t,” said Renu Malhotra, who serves as the Louise Foucar Marshall Science Research Professor and Regents Professor of Planetary Sciences at the University of Arizona.

“I think that’s the big thing Rubin is going to do — fill in the gaps in our knowledge of the interior of the solar system,” he added. “This will greatly improve our census and our knowledge of the interior of the solar system.”

As a result, astronomers are preparing for a flood of discoveries from this new frontier, which will shed light on many outstanding questions. Are there new planets hidden in the belt, or lurking beyond it? How far is this region extended? And are there traces of terrifying past encounters between worlds — both homegrown or from interstellar space — imprinted on this mostly pristine collection of objects from the deep past?

“I think this is going to be a very hot field soon, because of LSST,” said Amir Siraj, a graduate student at Princeton University who studies the Kuiper Belt.

The Kuiper Belt is a graveyard of planetary odds and ends scattered far from the sun during the solar system’s turbulent birth about 4.6 billion years ago. Pluto was the first KBO to be found, more than half a century before the belt was discovered.

Since the 1990s, astronomers have found several dwarf planets in the belt, such as Eris and Sedna, along with thousands of smaller objects. While the Kuiper Belt is not completely static, it is, for the most part, an intact time capsule of the early solar system that can be mined for clues about planet formation.

For example, the belt has strange structures that could be signatures of past encounters between giant planets, including a particular cluster of objects, known as a “kernel,” located about 44 astronomical units (AU), where an AU is the distance between Earth and the sun (about 93 million miles).

While the origin of this kernel is still unexplained, a popular hypothesis is that its components—known as cold classical—were dragged by Neptune on its outward migration of the solar system more than 4 billion years ago, which may have been a bumpy ride.

The idea is that “Neptune collided with other gas giants and made a small jump; this is called the ‘jumping Neptune’ scenario,” said Wes Fraser, an astronomer at the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, Canada’s National Research Council, who studies the Kuiper Belt. astronomer David Nesvorný came up with an idea.