Follow the Winter Olympic sportsPersonalize your feed

The Olympics have long been a platform for political posturing, with countries boycotting or banning them due to geopolitical conflicts.

But the International Olympic Committee (IOC) says that politics should stop once the Games begin — keeping the competitions and podiums free from political “interference”.

But what constitutes a nuisance can be complicated.

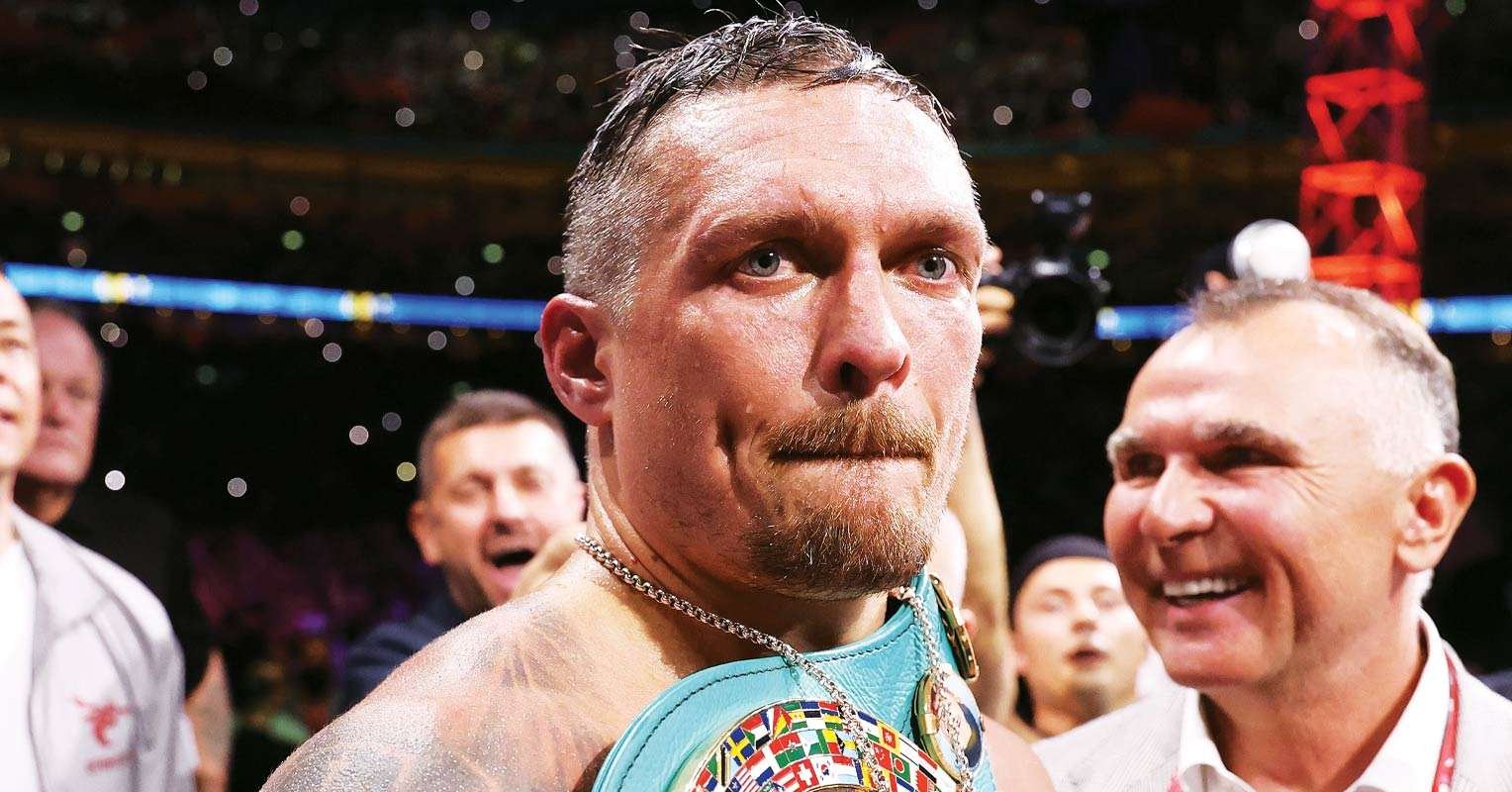

Even after the IOC banned Ukraine’s Vladyslav Heraskevych on Thursday — for wearing a helmet decorated with images of war victims — President Kirsty Coventry broke down in tears as she explained the decision, saying that although the helmet broke the rules, she disagreed with its “strong” message.

Heraskevych, a skeleton competitor, defied the IOC after being told he could not wear a helmet depicting Ukrainian athletes killed by Russia — a country banned from the Olympics since its 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Rule 50 came into effect as the IOC banned Vladyslav Heraskevych from wearing a helmet at the Winter Games.

Although the decision sparked outrage from Heraskevych’s teammates, the Olympic historian says it is in line with a strict interpretation of the rules.

“On the one hand, it’s a memorial to fallen comrades. It’s also a pretty explicit political statement about the nature of that war,” said Bruce Kidd, a former Olympic runner and professor emeritus at the University of Toronto, who writes about history and political economy of sport.

Athletes are allowed to make political statements off the field and ceremonies, including press conferences and social media. Some took advantage of it this year – above all, several American athletes who criticized their own country anti-ICE messages.

But Heraskevych says the rules have been unfairly applied to him, citing examples including the Israeli skeletonist Jared Firestone, who carried a statue bearing the names of the 11 Israeli athletes and coaches killed in the attack at the 1972 Games in Munich, Germany.

On the other hand, the IOC commissioned a two-man Haitian team this year to take off their opening ceremony jackets a picture of Toussaint Louverture, a former slave who was the leader of the revolution in Haiti some 200 years ago.

Kidd says enforcing these rules and defining what constitutes a political statement can be complicated and sometimes unclear.

Origin of the 19th century

The no-politics rules date back to the beginning of the modern Olympics.

In the 1890s, founder Baron Pierre de Coubertin envisioned the Olympics as part of a movement to foster global peace and understanding, Kidd says. Criticizing another country’s policies would undermine those efforts.

Still, some athletes “pushed those boundaries by speaking out, and other athletes, very subtly, made statements that anyone who knew the signs read as political statements,” he said.

Twenty athletes with Russian and Belarusian passports compete at the Winter Olympics, but do not represent the country. Here are the facts about ‘Individual Neutral Athletes’.

In one of the earliest and most dramatic examples, Irish track and field star Peter O’Connor—upset at having to compete for Great Britain because Ireland did not have its own Olympic committee—climbed a 20-foot flagpole at the 1906 Athens Games to raise an Irish flag that read “Erin Go Bragh,” or Ireland Forever.

The IOC did not punish him, although for other reasons it retroactively revoked those games from the status of official Olympic recognition.

Perhaps the most famous example occurred at the 1968 Summer Games in Mexico City, when American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who finished first and third respectively, wore black gloves and held fists in the air in a “Black Power” salute. on the podium.

They were suspended from the US team and forced to leave the Olympic Village.

Political statements have continued in recent years, albeit somewhat more quietly.

Canadian pentathlete Monica Pinette wore the Metis belt on 2004 at the closing ceremony in Athens, where she was the only indigenous competitor in the country. But in 2008 in Beijing, she he told the Globe and Mail she would not wear it again because officials have made it clear that they will strictly enforce rules related to political symbolism.

Ethiopian marathoner Feyisa Lilesa too I got an interview from the IOCbut escaped punishment, after crossing his arms at the finish line during the 2016 Rio Games, a protest gesture showing solidarity with his Oromo people.

In 2020, The IOC allowed German women’s field hockey player Nike Lorenz to wear a rainbow armband at the 2020 Tokyo Games as a sign of 2SLGBTQ+ solidarity, despite some saying it broke the rules.

Kidd says statements that don’t involve nation-state politics can be considered more acceptable, although he says enforcement over the years has been “full of contradictions.”

He says they are games it should be played in the spirit of liberal values and respect for other people, and the main point of banning politics is to try to avoid expressions of hatred or challenge that could incite state aggression.

“Trying to include the entire world of sports is complicated enough. But then you throw in all the differences and all the conflicts around the world, and you try to manage that in a way that will increase respect and understanding between people who hate each other,” Kidd said.

“It’s a real challenge. And it’s incredibly difficult now, when there’s so much tension and xenophobia in the world.”