These days, artificial intelligence can take notes during the doctor’s appointment, your confidence in school will increaseand helps to detect cancer (although LLMs not good at reading clocks). Now, new research turns to AI to understand a potentially ancient board game.

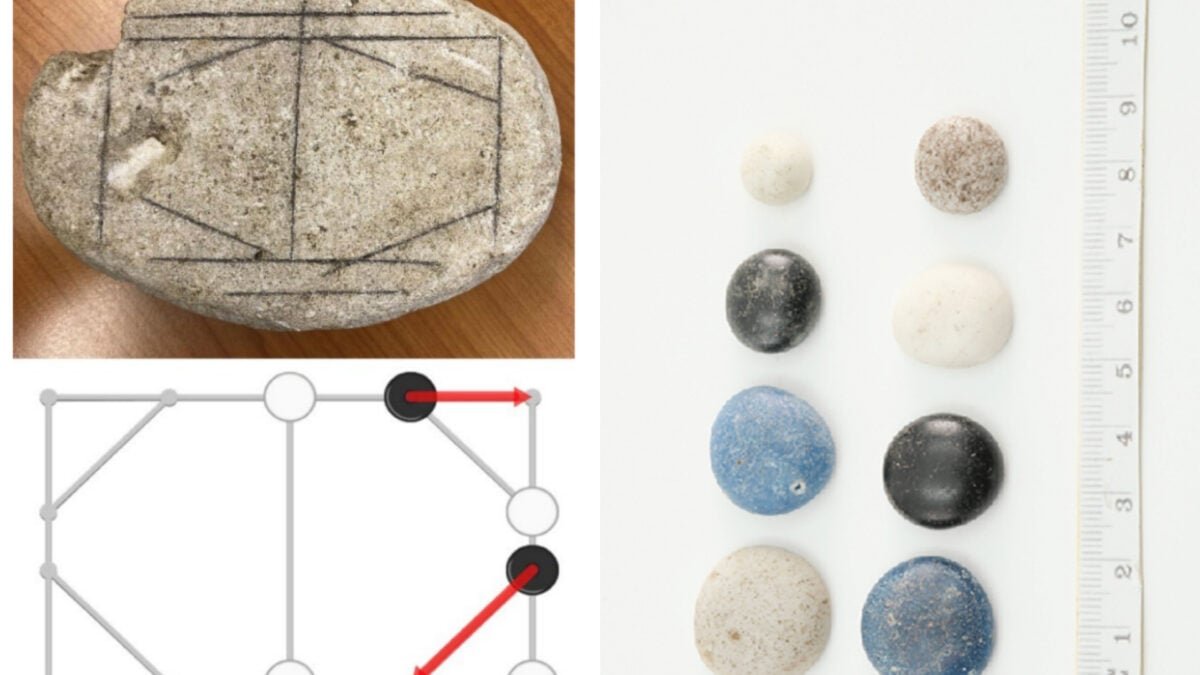

In the hands of a non-expert, the oval artifact doesn’t look like much of anything. However, the geometric patterns on one of its two broad sides, along with other clues, suggest that it was a stone game board. In a study published today in the journal Antiquity, researchers used artificial intelligence to test this theory, as well as to identify what the rules of the game are.

Those before us enjoyed board games, just like us; the hobby dates back to the Bronze Age, at least. The problem, however, is that the components of most of these games are not as durable as Monopoly houses and hotels can certainly prove. As such, the stone object unearthed in Coriovallum—a Roman town in the modern-day Netherlands—would be a rare opportunity to investigate for ancient nerds.

A mysterious ancient game

“We identified the object as a game because of the geometric pattern on its surface and because of the evidence that it was deliberately shaped,” Walter Crist, lead author of the study and an archaeologist at Leiden University who specializes in ancient board games, explained in a statement to Antiquity. “Further evidence that this is a game is presented by the visible damage to the surface consistent with abrasion caused by the sliding of game pieces during the Roman period on the surface.”

There is only one problem. The aforementioned geometric pattern does not match any game known to researchers. To investigate the matter, Crist and his colleagues did what most people do with a question these days—they asked an AI to test it. Due to human-induced abrasions on the artifact, the team used AI to model potential game rules.

“The damage is not evenly distributed across the board lines,” Crist said. “We aim to answer the question of whether we can use AI-driven simulated play as a tool to determine the rules of play that will mimic this non-uniform wear pattern on the inside of this board with rules similar to those documented for other small European games, thus proving that the object is likely a board game.”

AI vs. AI

The researchers had two AIs play a large number of ancient European board games, including Scandinavia’s Haretavl and Italy’s Gioco dell’orso, until they landed on one that could account for the stone board’s wear-and-tear.

This method finally reveals a game of blocking game, a type of board game whose objective consists of blocking the movement of another player (like Ticket to Ride, if you play like my bad partner). It also reinforces the earlier theory that the artifact is a board game after all.

“This is the first time that AI-driven simulated play has been used in concert with archaeological identification methods in a board game,” Crist concluded. “This research gives archaeologists the tools to identify games from ancient cultures that are not common or not commonly played, because current identification methods rely on connecting the geometric patterns that make up the playing field to games known today from textual references, or from their artistic representations.”

Interestingly, the previously known signs of blocking games only appear in Europe starting from the Middle Ages and are generally very rare in the region. In other words, the study suggests that people may have been playing these types of games centuries earlier than researchers thought.

What remains to be seen is how many tears have been shed and friendships broken because of the moving—or not—of the pieces on this board.