Women and girls are filmed using hidden cameras while using public or school bathrooms, undressing in changing rooms or relaxing at home. The recordings are posted in anonymous online chat groups, each with as many as 100,000 members from across China.

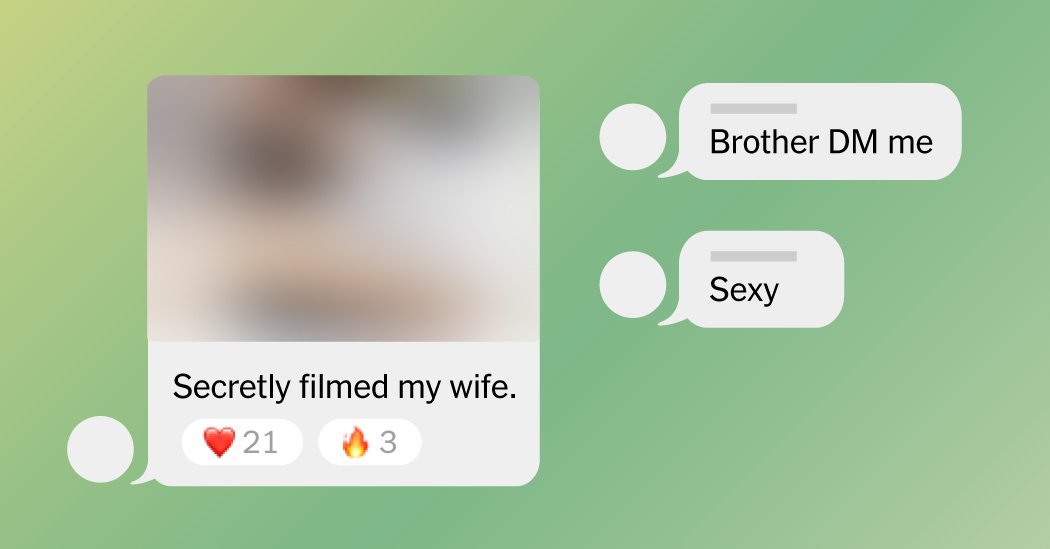

In one group, people post nude or semi-nude photos of women they describe as their current or ex-wives or girlfriends. One recent message, titled “secretly taken photos of wife,” included images of a woman lying in her nightgown, exposed from the waist down.

Group members also share explicit footage of the women they’ve captured in their lives.

A huge trade in secretly recorded videos of Chinese women and girls has flourished, fueled by the anonymity of Telegram, the availability of hidden cameras and the convenience of Chinese online payment apps. People share and exchange photos and videos of their girlfriends, wives, relatives and acquaintances – a practice known in Chinese as “toupai chumai,” or “secret recording of treason”. They also trade in such recordings of foreigners.

Globally, the proliferation of such content sharing without consent, a form of what the United Nations describes as digital violence against womenit has prompted new laws and enforcement in many countries. But in China, the authorities have not publicly condemned such groups or announced investigations into them even after they came to light.

The lack of enforcement is striking for a country known for expansive internet surveillance and the ability to track users across platforms, including overseas services. Instead, activists say, officials began censoring discussions on the issue, blocking searches and silencing those who tried to warn women or pressure them to do something.

Some chat groups target young girls. On one Telegram channel that has more than 65,000 members, for example, there was a discussion about installing hidden cameras in elementary school bathrooms.

Underground industry in plain sight

The footage is often described by those who market it as being captured by hidden cameras or cell phones, or obtained from hacked surveillance systems. Videos taken secretly up women’s skirts, also known as “upskirting”, often appear in these groups.

A Telegram channel posted a five-minute video in September showing a woman in a dress walking through what appears to be an airport in the city of Chengdu. The camera, set at a low angle, zooms in on the woman as she waits in the check-in line until it is under her skirt. He stays hooked on her crotch for almost a minute before pulling away.

Other groups post videos of women or girls taken in schools or public institutions such as hospitals.

Secret recordings are used to trick people into paying for access to private channels by promising more content. Group members also exchange tips on the best cameras and how to hide them in water bottles, trash cans and other hiding places.

This store is booming on Telegram because it is known for its minimal monitoring of illegal content. Telegram is blocked in China, but is accessible through virtual private networks that route the Internet connection outside the country.

The use and sale of hidden cameras is illegal in China, but on Chinese short video platforms Kuaishou and Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, companies openly sell small pinhole cameras, with ads showing women in nothing but their underwear. Kuaishou and Douyin did not respond to requests for comment.

Private Telegram groups for sharing secretly recorded videos of women and girls pay through popular Chinese digital payment systems Alipay and WeChat Pay as well as the cryptocurrency Tether. One group offers access to more than 40,000 videos secretly recorded from hotels, homes and public restrooms for a $20 “VIP” membership.

Alipay and WeChat Pay did not respond to questions about allowing payments for secretly recorded content, but said they have banned transactions related to illegal activities. Telegram said it has a “zero tolerance policy” for material depicting child sexual abuse and a “strict policy” against non-consensual pornographic images. Tether said that when its stablecoin is linked to criminal activity, the company will cooperate with law enforcement agencies.

Perhaps the biggest reason the industry has been able to thrive, according to Chinese citizens who researched these forums, is government inaction.

In South Korea, the discovery of a similar network of Telegram chat rooms sharing exploitative videos of women and girls, known as the “Nth Room” scandal, led to prolonged protests prison sentences for included changes in the law. In the United States in May, President Trump signed into law Removal Act, criminalizing sharing intimate images without consent and requiring platforms to remove them.

In China, a public outcry erupted last summer when a woman exposed a Telegram forum called MaskPark where people shared sexually explicit videos of their current and former partners, as well as other women and girls they know. The woman discovered the channel, which had more than 80,000 members and dozens of sub-groups with more than 300,000 members, after learning that her ex-boyfriend had been sharing her photos and videos there.

“It put Chinese women on notice that they are not safe in their everyday environment, when they travel, even when they are with their partners,” said Lin Song, a senior lecturer in gender studies at the University of Melbourne.

Yet despite the furore on Chinese social media, government officials have remained silent. Groups like MaskPark continue to operate. China’s Ministry of Public Security, the main law enforcement agency, did not respond to requests for comment.

That episode prompted women like Cathy, a recent graduate from Guangdong province living abroad, to try to find the people behind MaskPark. Cathy, who asked to be identified only by her English name out of concern for her own safety, said she sent information to China’s internet regulator with screenshots from within the group.

“If they wanted to investigate, they had a ton of leads to follow,” she said.

Small enforcement

Under Chinese law, legal tools to deal with secret recording are limited. Producing or distributing pornography for profit is a crime punishable by prison, but filming people without their consent is not a crime in itself.

As a result, secret recording cases are usually treated as minor public security violations, according to Zhou Chuikun, a lawyer at the Beijing-based Yingke Law Firm, punishable by up to 10 days in jail and a fine of about $140. (If such explicit footage is shared or sold, fines can go up to $700.) He said that because Telegram is hosted outside of China, researching its users and gathering evidence could be difficult.

“It is very difficult for victims to defend their rights,” he said.

Lao Dongyan, a prominent law professor in Beijing, criticized the Chinese legal system’s fixation on obscenity, which she argued came at the cost of women’s rights in the MaskPark case.

“The women caught in these recorded videos are the primary victims,” she wrote on Weibo. “Treating these videos simply as obscene material is tantamount to treating them as parties involved in pornographic work. It’s absurd.”

Using VPNs masks users’ IP addresses in China. But the Chinese police are in the past identified the protesters and government critics who used foreign platforms including Telegram.

Chinese police have also arrested people for posting pornography on these platforms. Last year, a court in Shanghai handed down a suspended eight-month prison sentence to a man surnamed Xu for posting pornographic videos on X and Telegram, where he charged people for the content. Authorities used Alipay and WeChat Pay transaction data as evidence against him, the ruling said.

Authorities in China have many tools to investigate these abuses because domestic payment systems require users to register for accounts with their real names, and police units are embedded in these companies, according to Maya Wang, deputy Asia director at Human Rights Watch.

“The Chinese government has much greater access to people’s personal information compared to many other police forces around the world,” she said. “If that’s a priority, I’m sure they can be tracked.”

Telegram’s features, including its large groups, encryption capabilities, and opposition to government interference, have made it a a haven for criminals as well as dissidents. The company rarely responds to government requests for information.

Telegram said it deleted the MaskPark group in March 2024. But groups using the same name and sharing similar content were active until last July. New ones have also appeared, several of which claim to be original.

Telegram searches using Chinese terms related to secret recordings turned up more than 200 groups with “secret recording” in their names. The New York Times confirmed more than 30 active Chinese-language groups where members or administrators regularly posted videos of women and girls that were described as secretly filmed.

In one channel founded in November that used the name MaskPark, the group’s administrator told members to keep quiet for a few days. “Otherwise we might get banned again,” the administrator said.

Silencing those who speak

People like Cathy who try to draw attention to the problem seem to be being silenced by the Chinese authorities.

On Chinese social media, search terms related to MaskPark were blocked. Cathy and two other activists The Times spoke to said their posts about the secret recording issue had been removed and their accounts muted or suspended. Chat groups on WeChat to warn women and expose groups like MaskPark have also disappeared.

“I feel like the whole government is silencing everyone, preventing them from speaking and spreading the word,” said Cynthia Du, a 23-year-old from the eastern province of Shandong.

The fight for women’s rights is increasingly sensitive in China, where the government sees feminism as disruptive, especially as officials push women toward more traditional roles in hopes of reversing a declining birth rate.

As a result, calls for action have been met with suspicion, with some online commentators accusing feminists of inventing MaskPark as a way to smear the Chinese. Cathy and Ms. Du have received messages from anonymous netizens threatening to reveal their personal information online.

When Cathy posted an ad online seeking volunteers for MaskPark research, she received an email with a list of women and their personal information. “Bitch, you’re next,” the message read.

Cathy is worried about being doxxed. But she was also encouraged by dozens of people who want to help expose these groups.

Among those who messaged her are experts in blockchain technology, law and cybersecurity, as well as other Chinese women living abroad who can better access Telegram and other sites. A woman sent her book notes about the Nth Room incident in Korea and what Chinese activists can learn from it.

“Other people didn’t give up,” she said, “so I shouldn’t either.”

Berry Wang contributed reporting.