Despite the rising valuations of the Magnificent Seven and concern over the huge cost of AI capital, a top economist argues that the US stock market is missing the most critical ingredient of a financial mania: the exit of “smart money.”

Owen Lamonta portfolio manager at Acadian Asset Management and a former finance professor at the University of Chicago, said that while the market looks and feels like a bubble, we are not currently in an AI bubble. As he spoke luck from his office in Boston, the S&P 500 crossed 7,000 for the first timebut he did not fail. For Lamont, the sign of a bubble is the issuance of equity, when corporate executives, the ultimate insiders, rush to sell overvalued stock to the public.

“Part of the reason I don’t think there’s a bubble is that I don’t see the smart money as acting like a bubble,” he said. luck. “I would probably say there is no bubble yet.”

In his view, the smoking gun for the formation of the bubble is companies going public and selling equity. That’s a game for dumb money, he added.

Lamont—who also teaches at Harvard, Yale and Princeton, and blogs for Acadian under the moniker Owenomics— dialed back some classics in financial history to make his point.

“The one thing we see in the bubbles is to return to South Sea Bubble in 1720 issuance,” he said. For readers who are not financial historians, Lamont refers to a joint stock company from the beginning (or earlier) days of capitalism, involving the financing of the United Kingdom during the War of the Spanish Succession.

Issuance and the other three horsemen of the bubble apocalypse

In 2026, the flood of new shares did not hit the market, as happened during the dotcom crash of 2000 and the speculative frenzy of 2021, which Lamont considers a bubble, unlike most of his peers. Corporations are doing the opposite of that today. Last year, US companies engaged in approximately $1 trillion worth of stock buybacks, Lamont said, as he detailed in his November blog post, “A trillion reasons we are not in an AI bubble.” Companies are the smart money, he explained, and if they’re selling equity, that’s a sign that equity is overpriced. But open float shares are shrinking.

Lamont’s bubble analysis framework relies on the “Four Horsemen”: overvaluation, bubble belief, issuance, and outflows. While he admitted that three of them will be in the market in early 2026 — valuations are high, retail investors are rallying, and sentiment is faltering the absence of issuance disqualifies the current cycle from bubble status. In fact, it’s “baffling” that there are no more IPOs. “They haven’t arrived yet and they will probably arrive in 2026,” he said. In 1999, for example, the market absorbed more than 400 IPOs. And in 2021, the market is flooded with SPACs and meme stocks. Now, the scene is very quiet.

The economist explained that he developed this framework from his “strange background,” an initial academic interest in corporate finance derived from his curiosity about the causes of the Great Depression. “I wouldn’t say that my four horsemen are the only way to do it or the best way to do it, but they are the way that seems most empirically relevant to me.”

And with a bit of historical perspective, Lamont noted that US stocks may be expensive but they’re not at dotcom extremes. He graduated from college in 1988, and remembers the Japanese stock market bubble as truly “unbelievable” at that point, worse than any situation today. He mentioned the famous Shiller CAPE ratio. One of the many signs made by the Nobel prize winning economist Robert Shillerit divides a stock or index price by its 10-year average of inflation-adjusted earnings per share, kind of a long-range view of the classic price-to-earnings ratio. At its peak in 1999, Lamont said, CAPE was 45, and now it’s 40, but Japan over 90 in the late ’80s.

Lamont recalled a paper released at the time from two finance professors, James Poterba and Ken French, called “Are Japanese Stock Prices High?” A year ago, the title should be changed to past tensebecause the market has collapsed so much.

When Lamont taught at the University of Chicago in the mid-1990s, he added, he found himself believing that the market was mostly efficient, but what he saw then brought him closer. behavioral economics. “Bubbles are a behavioral phenomenon and they consist of people making cognitive errors,” he said. In 1996, he produced academic research that argued the market was overvalued — to see the S&P 500 double and the NASDAQ triple in the next few years. He suggested we might be in a similar position today: “We might be in the first innings” of the AI story.

When the dotcom bubble burst, Lamont added, he and many of his peers were shocked. “I would say that it really changed our view of whether the market is rational. And I remember going to academic conferences, like in 1999, and … many, many finance professors were like, ‘This is crazy, it doesn’t make sense, it’s getting out of hand.'” A few years later, he added, speaking slowly to be precise, “it’s not really changing their assets … it’s really true that only those can change their it is the mind that changes their mind.”

The weird and wonderful world of peak-bubble IPO fraud

“I define a bubble as the price goes up and people trade, own, buy an asset that they believe is overvalued,” Lamont explained.

While this market has the preconditions—a revolutionary technology and extraordinary income growth—the cycle has not yet reached the terminal phase where insiders are rushing out. In his scenario, the Nasdaq 100 doubled in one year and the Shiller CAPE ratio soared to 80, echoing Japan in 1989.

“One of the strange things about the IPO market is that you don’t have to be a good IPO company. You just have to have gullible investors who think you’re a good company,” Lamont said, jokingly. He asked hypothetically, where are the fraudulent companies in the market today? “We have a lot of fraudulent companies in 2021, so I’m disappointed by the lack of creativity of white-collar criminals,” he added, tongue planted in cheek.

While skeptics worry that Big Tech’s billions in AI spending will yield poor returns, Lamont said he sees it as a “reasonable gamble” rather than speculative mania. He compared the current AI build-out to drilling for oil: an expensive investment with uncertain viability, but a reasonable corporate strategy nonetheless. He also compared it to another famous high-risk capex cycle: railways, arguing that such developments usually occur in the early or middle stages of transformative technologies, not only at the end.

“I think it’s fair to say that (the hyperscaler companies) are building a lot of data centers and they don’t need them,” Lamont said, referring to the center of the potential AI bubble concentrated around. Nvidia and OpenAI, with Microsoft and Oracle orbiting. “But that doesn’t mean it’s unreasonable on its face, and it doesn’t mean they’re overvalued right now.”

Many new technologies have resulted in overbuilding, such as building more railroads and building more oil wells, but that doesn’t guarantee a bubble either. “Historically, it’s true that in times when there’s a big wave of capex, that’s not a good time to invest in the stock market. That’s when the market is overvalued.” When asked if investors should buy gold again, coming days after it first passed $5,000 an ounce, Lamont replied, “I don’t know about that.”

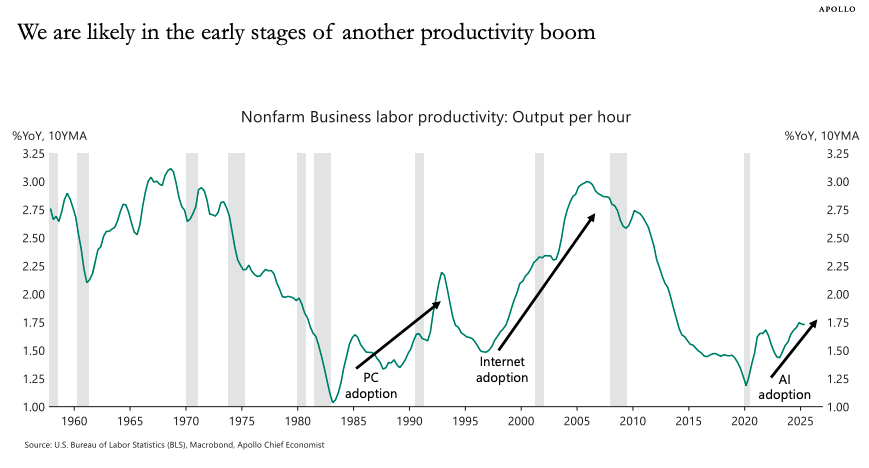

To Lamont’s point, many leading market watchers believe this is an AI boom, not a bubble, along with Apollo Global Chief Economist Torsten Slokfor example, releasing a chartbook likened the productivity boom from AI to the adoption of PCs and the internet. “While there are questions about the magnitude of the impact at the macro level,” Slok writes, “it is clear that there are already significant impacts in sectors including DevOps software, robotic process automation and content management systems.”

An IPO mega-cycle?

For those looking for the end, Lamont suggests keeping an eye on the calendar for 2026. If high-profile private companies want SpaceX finally decided to go public, prompting a wave of copycat IPOs, the “smart money” may have finally tipped the scales.

Terrible, as Lamont spoke luck, THE Financial Times reported which is the world’s largest private equity firm, Blackstoneis gearing up for a blockbuster year for IPOs. Jonathan Gray, president of the asset management giant, said FT that 2026 constitutes “one of our largest IPO pipelines in history.”

Similarly, Kim Posnett, the co-head of investment banking at Goldman Sachs, recently predicted in a Q&A with luck that the market is entering an IPO “mega-cycle” defined by “unprecedented deal volume and IPO sizes.” He distinguished it from the two periods Lamont referred to, the late ’90s dotcom wave and the 2020-21 surge, saying the “next IPO cycle will have more volume and the biggest deals the market has ever seen.” As announced, The Wall Street Journal reported on Thursday that OpenAI plans to go public in the fourth quarter of 2026, citing people familiar with the matter.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com