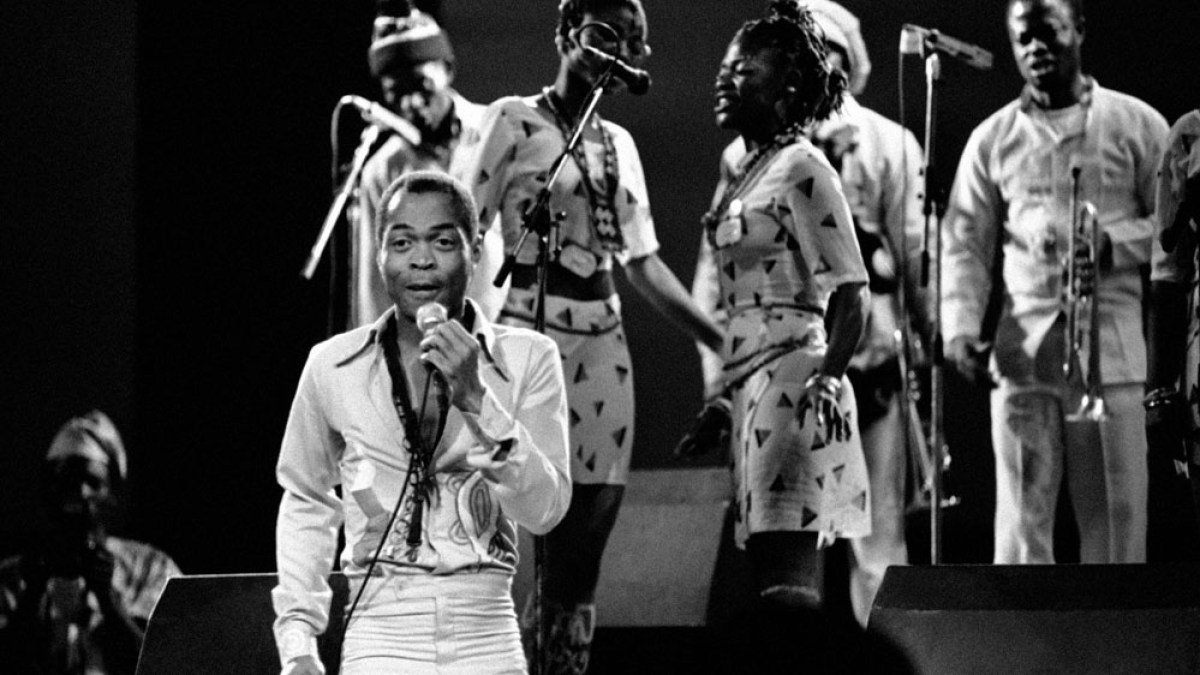

Thirty years after his death, the “Father of Afrobeats” Fela Kuti made history as the first African to win a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

The Nigerian musician, who died in 1997, was honored along with several other artists at a ceremony in Los Angeles on Saturday on the eve of the 68th Grammy Awards.

Recommended Stories

3 item listend of list

It was an honor for his family and friends, some of whom were in attendance, who hoped to help spread Fela’s music and ideology among new generations of musicians and music lovers. But they also admit the admission comes too late.

“The family is happy about it. We are happy that he is finally recognized,” Fela’s daughter Yeni Kuti told Al Jazeera before the ceremony. “But Fela never got a (Grammy) nomination in her life,” she lamented.

She said such recognition was “better late than never” but “we still have a long way to go” in terms of equitably recognizing musicians and artists from the continent.

Lemi Ghariokwu, a renowned Nigerian artist and designer of 26 of Fela’s iconic album covers, said this was the first time an African musician had received the honor and “it goes to show that whatever we Africans need to do, we need to do it five times more.”

Garrioku said he was “honored” to witness the moment for Fela. “It’s great that one of us can be represented in this category, at that level. So, I’m excited. I’m happy about it,” he told Al Jazeera.

But he admitted he was “surprised” when he first heard the news.

“Fela is totally anti-establishment. Now the powers that be are recognizing him,” Garrioku said.

As for what Fela’s reaction to the award would have been if he were still alive, Garrioku said he thinks he would be delighted. “I can even imagine him raising his fist and saying, ‘Look, I’ve got them now, I’ve got their attention!'”

But Yeni feels her father will be largely unaffected.

“He didn’t[care about the award]at all. He didn’t even think about it,” she said. “He played music because he loved music. To be recognized by his people – human beings, fellow artists – that made him happy.”

Yemisi Ransom-Kuti, Fela’s cousin and the patriarch of the Kuti family, agrees. “Knowing him, he’d probably say, you know, thanks, but no thank you, or something like that.” She laughed.

“He really wasn’t interested in popular opinion. He wasn’t driven by what others thought of him or his music. He was more focused on his own understanding of how it impacted his career, his community and his continent.”

While she believes the award may not mean much to him personally, she told Al Jazeera he would recognize its overall value.

“He would recognize that it would be a good thing for these institutions to start giving due credit across the continent,” Ransome-Kuti said.

“There are a lot of great philosophers, musicians, historians – African – who haven’t been brought to the forefront and given the attention they deserve. So I think he would have said, ‘Okay, great, but what happens next?'”

“Fela’s influence spans generations”

Fela was born in 1938 in Ogun State, Nigeria, as Olufela Olusegun Oludotun Ransome-Kuti (later renamed Fela Anikulapo Kuti). His father was an Anglican priest and school principal. activist mother.

In 1958 he went to London to study medicine but transferred to Trinity College of Music, where he formed a band that fused jazz and high life.

Returning to Nigeria in the 1960s, he went on to create the Afrobeat music genre, which blended high life and Yoruba music with American jazz, funk and soul. This laid the foundation for Afrobeats – a genre that later blended traditional African rhythms with contemporary pop music.

“Fela’s influence spans generations, inspiring artists such as Beyonce, Paul McCartney and Thom Yorke, and shaping modern Nigerian African music,” citation Included in this year’s list of Grammy Special Merit Award winners.

But beyond music, he was a “political radical (and) outlaw,” the citation adds.

By the 1970s, Fela’s music had become a vehicle for fierce criticism of Nigeria’s military rule, corruption and social injustice. He declared his Lagos commune, the Republic of Kalakuta, independent of the state – a symbolic rejection of Nigeria’s authority – and released the scathing album Zombie in 1977, with lyrics depicting soldiers as mindless zombies without free will. Subsequently, the army raided Kalakuta and brutally attacked local residents, leaving Fela’s mother injured.

Arrested and harassed frequently throughout his life, Fela became an international symbol of artistic resistance, and Amnesty International later recognized him as a prisoner of conscience after his politically motivated imprisonment. When he died in 1997 at the age of 58, an estimated 1 million people attended his funeral in Lagos.

Yeni and her siblings are now the custodians of her father’s work and legacy. She runs the African Rhythm Center,

New Africa Shrine in Ikeja, Lagos and hosts an annual celebration in honor of Fela called “Felabration”.

She remembers growing up with her legendary father feeling “normal” because it was all she knew. But she also said that “I was in awe of him” as an artist and thinker.

“I really admired his ideology. The most important thing to me was African unity… He completely adored and admired (former Ghanaian President) Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, who fought for African unity. I always said to myself, can you imagine if Africa united? How far we would have gone; how far we would have progressed.”

Reflecting on Fela’s legacy, artist Ghariokwu said most of today’s big Afrobeat musicians are influenced and inspired by Fela’s music and fashion.

But he lamented that most people “never really sat down and thought about the ideological part of Fela – Pan-Africanism – they never really examined it”.

For him, Fela’s Grammy recognition should say to young artists: “If someone who is completely anti-establishment (like Fela) can be recognized in this way, maybe I can express myself too without having too much fear.”

Yeni said that through Fela’s work and life philosophy, he wanted to convey a message of African unity and political awareness to young people.

“So maybe with this award, more young people will be attracted to talk more about this issue,” she said. “Hopefully they will engage with Fela more and hopefully talk about progress in Africa.”