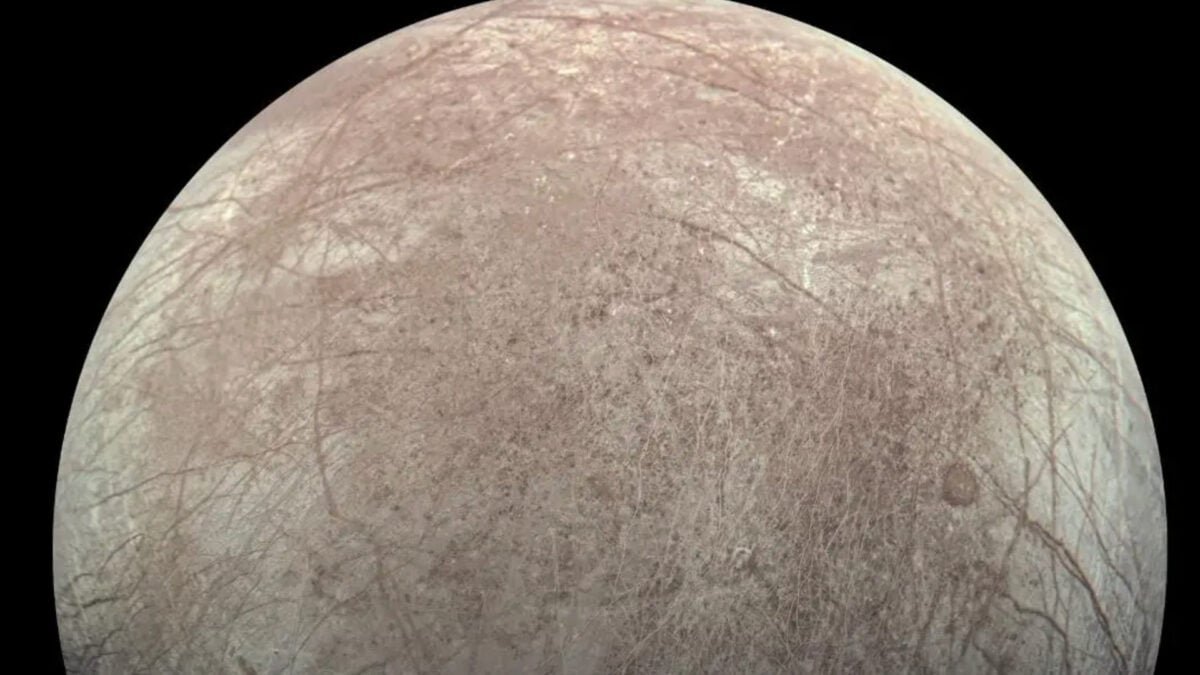

Europeone of Jupiter’s 95 moons, is encased in a shell of water ice, and researchers have recently estimated its thickness.

In 2022, NASA’s Juno spacecraft zooms close to the moon’s surface. Information from this flyby led researchers to conclude that, in the area where the flyby collected data, the moon’s ice layer was on average about 18 miles (29 kilometers) thick. The new measurement, along with other new information about some parts of the ice, may inform our understanding of the moon’s potential habitability.

A 2022 flyby

“The 18-mile estimate is related to the cold, rigid, conductive outer-layer of a pure water ice shell,” Steve Levin, Juno project scientist and co-investigator from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), told an agency statement. “If there was an inner, slightly warmer convective layer as well, which is possible, the total thickness of the ice shell would be even greater. If the ice shell contained a small amount of dissolved salt, as some models suggest, then our estimate of the thickness of the shell would be reduced by about 3 miles (4.8 km).” JPL manages the Juno mission.

Juno recorded this data on September 29, 2022, using the Microwave Radiometer (MWR). The flyby brought the spacecraft within about 220 miles (360 km) of Europa, with the MWR gathering information from about 50% of its surface. In the search for other habitable worlds within our solar system, scientists are particularly interested in Europa, which is believed to have salty oceans (which may hold the ingredients for life). Learning more about the ice shell on the surface will help us to know what happens under the surface of the moon and how likely it is to have an environment where life can exist.

Areas of shallow ice

In addition, Juno’s flyby also identified features called “scatterers,” such as cracks, pores, and voids, in the ice near the surface—features that, as the name suggests, scatter the MWR’s microwaves as they bounce off the ice. Researchers believe it is at least several inches in diameter.

The team’s estimation of a thick shell suggests that oxygen and nutrients must begin a longer journey between the surface of the moon and its potential ocean, and the study shows that the dispersants are probably not an important route in this context. Understanding this connection will be important for future research on European settlement.

Shelter, shelter, shelter

“How thick the ice shell is and the presence of cracks or pores within the ice shell are part of the complex puzzle to understand Europa’s habitability potential,” explained Scott Bolton, Juno’s principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute. He and Levin are co-authors of a study was published in December in the journal Nature Astronomy. “They provide critical context for NASA’s Europa Clipper and the ESA (European Space Agency) Juice (JUpiter ICy moons Explorer) spacecraft—both of which are headed for the Jovian system.”

So, Europa’s icy crust is thicker than we thought. And with each new data point, scientists are getting closer to unlocking the moon’s hidden secrets. Eventually, we may finally solve the mystery of whether life ever existed on this fascinating frozen world—and whether it still exists today.