Lebanon’s cabinet has approved a draft law that could return depositors’ money after six years of the world’s worst financial crisis.

In 2019, the Lebanese currency began a spiral of appreciation. Banks locked their doors to prevent depositors from withdrawing their funds.

Recommended Stories

3 item listend of list

Some depositors were forced to stay at bank branches to withdraw their money.

By the time the currency was regulated, the Lebanese lira had lost 98% of its value.

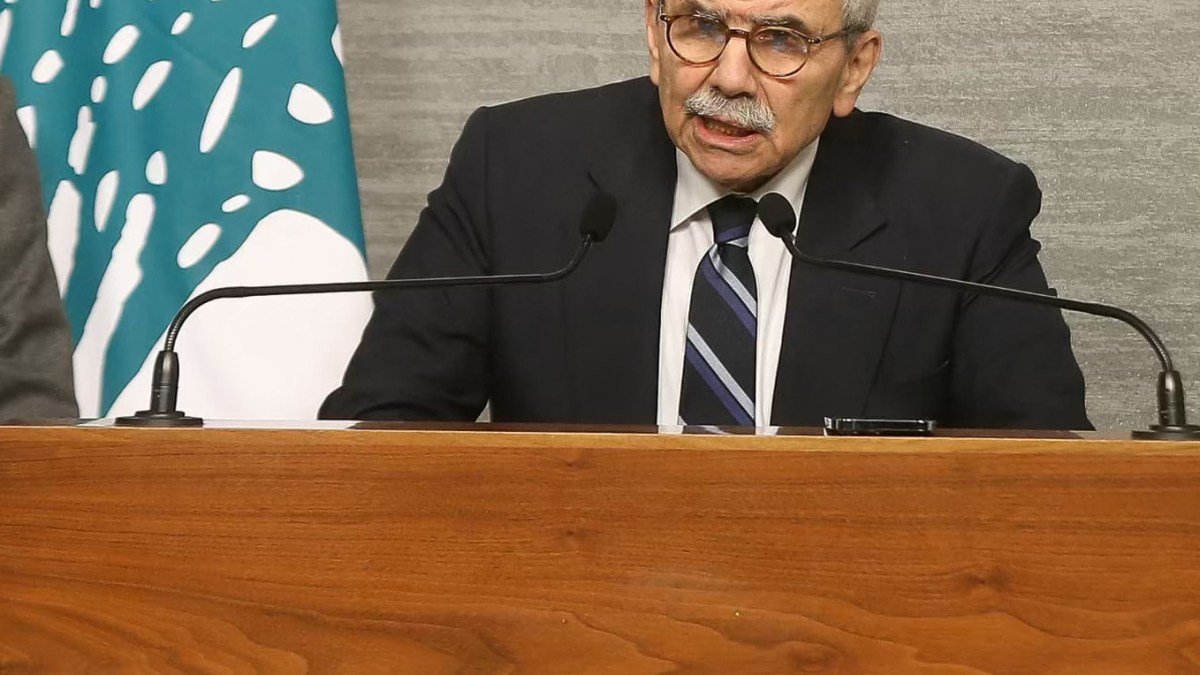

To address the issue, Lebanon’s cabinet is passing a so-called “gaps law”, which is expected to be signed by the prime minister and president before being submitted to parliament for debate.

Here’s everything you need to know about the so-called “Law of the Gap.”

What are the benefits of law?

Depositors will get some of their money back.

By law, anyone who deposits up to $100,000 will be repaid within four years. This is an improvement over past proposals, which took more than a decade to repay the same amount.

However, observers point out that a plan proposed in 2020 under the government of former Prime Minister Hassan Diab saw savers receive as much as $500,000 back.

“This is probably the biggest opportunity lost and this was done to protect the banks,” Fouad Debs, a lawyer and member of the Depositors’ Union, told Al Jazeera.

Prime Minister Nawaf Salam said a comprehensive financial audit should also be conducted.

“Forensic audits … mean that (banks) are going to disclose all of their operations — dividends and bonuses paid to executives — basically all the financial engineering that they do,” Debus said.

He added that the audit is important because “there are a lot of discrepancies between what they say and what the state says.”

What’s wrong with this?

a lot of.

First, the $100,000 figure is per depositor not per account. So if someone has two accounts worth over $100,000, they’ll still only get $100,000 back.

Prime Minister Salam said depositors with more than $100,000 in their accounts would receive $100,000 in cash and the remainder in central bank-backed bonds.

Who does the draft law benefit? Who does it punish?

Under the current draft of the law, bankers, banks, and the politicians aligned with them would get off fairly easily, while the state would bear much of the burden of the financial collapse.

Under the current version of the draft law, banks are only responsible for paying out 40% of withdrawals, despite their role in causing the financial crisis.

But banks, bankers and affiliated politicians are still mounting media campaigns and lobbying parliament to attack the law and make it more favorable to them.

Under the new draft law, banks would be required to pay far more than they currently pay, but still far less than critics say they should pay.

These claims lack clarity.

During the crisis, banks were still able to pay dividends to shareholders and bonuses to executives, while regular savers were unable to access funds for everyday expenses such as buying food or paying bills.

“Depositors should be the last ones who have to pay,” Debs said.

How much will the state have to pay?

The state must close the “gap” between what Lebanese banks owe their depositors and what the Lebanese financial system can pay.

The shortfall is currently estimated at $70 billion.

Who do the bankers think should pay for all this?

They say the state should pay. Many bankers and banks said they entrusted the money to the Central Bank of Lebanon (BDL), which gave it to the state, but the state lost the money. Therefore, the country should pay the price.

But critics argue that many banks hand over depositors’ money to BDL without asking depositors.

“They put it there because the banks made a lot of money and benefited greatly from it,” Debus said. “They’re putting all their eggs in one basket … the banks are very aware of that.”

How does the state pay?

Essentially using public funds. After cash is provided to depositors, everything else is repaid in the form of bonds backed by the state and its assets, including Lebanon’s gold reserves.

Critics say this is problematic because many of Lebanon’s current bonds are sold to foreign vulture funds. So state assets can essentially be used to pay off vulture funds or pay off big savers at the expense of the entire Lebanese population.

What is the IMF saying?

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) usually calls for austerity, but this time civil society and the IMF are on the same page.

“The IMF said… ‘How can you make depositors pay before bankers do?'” Debs said, adding that the IMF’s stance showed “how greedy and vicious the ruling elite is here.”