Reuters

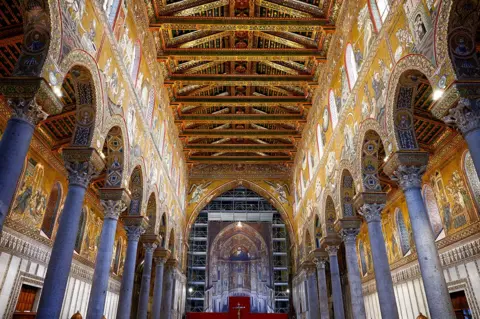

ReutersOn a hill in Sicily, overlooking the city of Palermo, sits a little-known gem of Italian art: the Cathedral of Monreale.

Built during the Norman rule in the 12th century, it has the largest collection of Byzantine-style mosaics in Italy, the second largest in the world after Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

Now, this UNESCO World Heritage Site has undergone extensive restoration and has been restored to its former glory.

Monreale’s mosaics are designed to impress, humble and inspire visitors walking along the central nave, emulating the style of Constantinople, the surviving capital of the Roman Empire in the East.

They cover an area of over 6,400 square meters and contain approximately 2.2 kilograms of pure gold.

Reuters

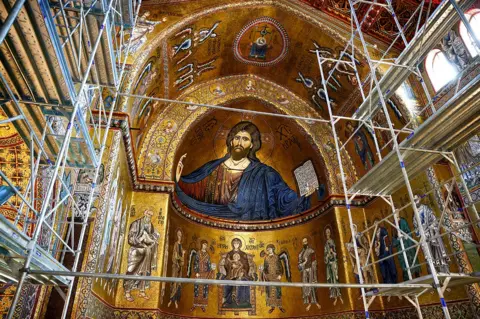

ReutersRestoration work lasted more than a year, during which time the cathedral became a construction site, with a maze of scaffolding erected over the altar and transepts.

Local experts from the Italian Ministry of Culture led a series of interventions, starting with removing the thick layer of dust that had accumulated on the mosaics over the years.

They then repaired some tiles that had lost their enamel and gold leaf, making them look like black spots from underneath.

Finally, they intervened and fixed the areas where the tiles were peeling from the wall.

Father Nicola Gallio said making the mosaics was a challenge and a great responsibility.

He has been a pastor here for 17 years and has been keeping a close eye on the restoration work like a concerned father.

“The team does this almost tiptoeing,” he told me.

“Sometimes, unforeseen issues arise and they have to suspend operations to find solutions.

“For example, when they got to the ceiling, they realized it had been covered in a layer of varnish that had yellowed. They had to peel it off, quite literally, like plastic wrap.”

Odebel

OdebelThe mosaic was last partially restored in 1978, but this time the intervention was more extensive and included the replacement of the old lighting system.

“The system at that time was very old. The lighting was dim, the energy costs were extremely high, and it simply did not reflect the beauty of the mosaics,” says Matteo Cundari.

He is the regional manager of the company Zumtobel, which was tasked with installing the new lights.

“The main challenge was to ensure that we highlighted the mosaics and created something that met the various needs of the cathedral,” he added.

“We also wanted to create a fully reversible system that can be replaced in 10 or 15 years without damaging the building.”

Odebel

OdebelThe first projects cost 1.1 million euros. A second project is being planned next, focusing on the central nave.

I asked Father Gallio how it feels to see the scaffolding finally removed and the mosaics taking on a new light. He smiled and shrugged.

“When you see it, you’re so struck with awe that you can’t really think about anything. It’s pure beauty,” he said.

“Being a guardian of a world heritage like this is a responsibility. The world needs beauty because it reminds us of the beauty of our humanity and reminds us of what it means to be men and women.”