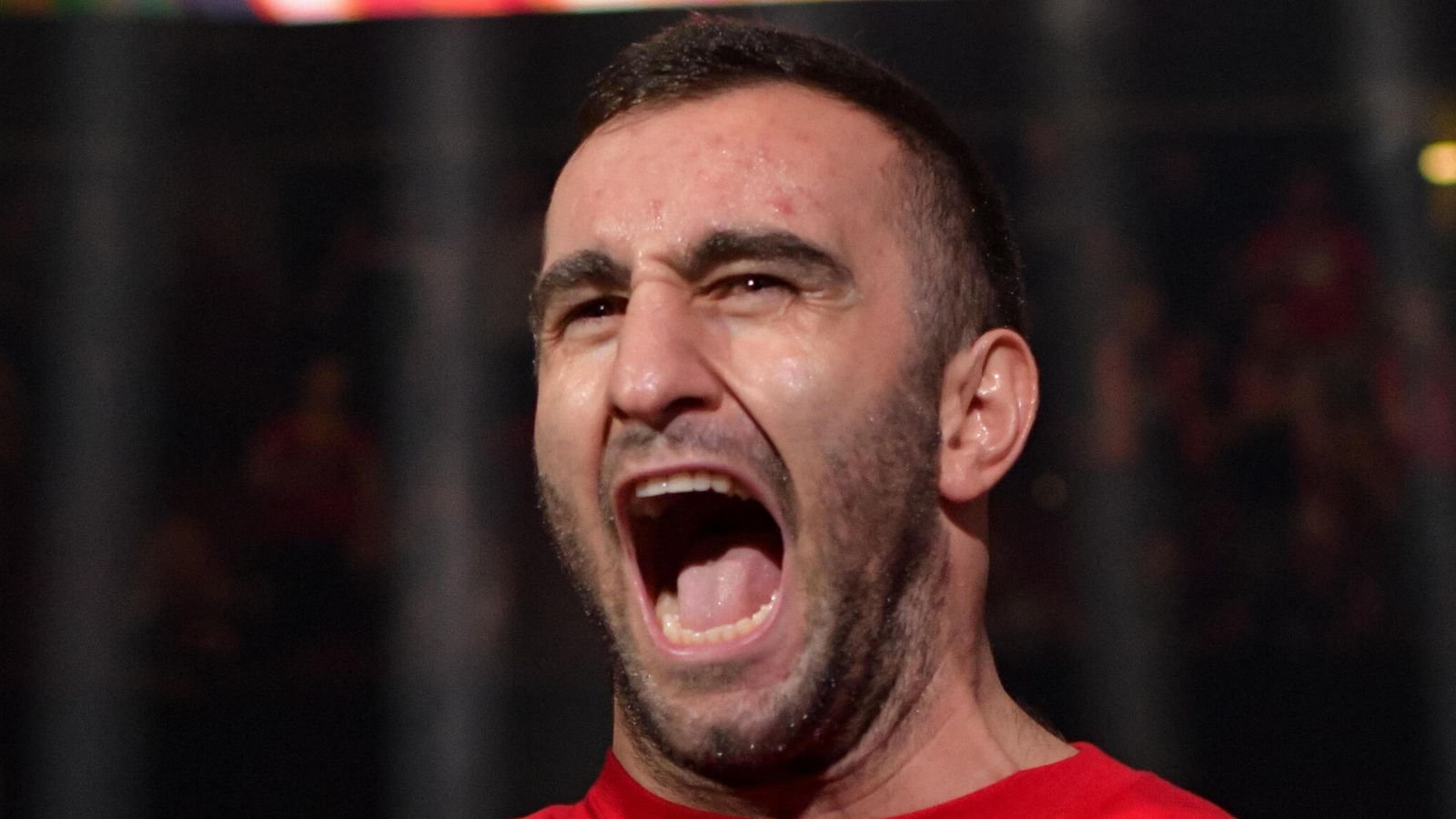

On a recent morning in Syria’s Latakia province, more than a hundred former soldiers stood silently, their eyes wide and wary as they waited to register with the new rebel rulers of country. A tired man walks around with a poster of ousted president Bashar al-Assad on a stick, asking men to spit on it. Everything is obligatory.

Since taking power this month, the new interim government – led by the Islamist rebel group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham – has established several of these so-called settlement centers across the country, placing the a call for former soldiers to visit, register for no. -military ID and surrender their weapons.

They say initiatives like these will help ensure security and begin the process of reconciliation after 13 years of brutal civil war that has left the country riddled with weapons and armed factions.

“The most important thing is to disarm the people,” said Abdel Rahman Traifi, the former rebel who now runs the center. “That’s the only way you can guarantee security.”

Yet in Latakia, the Assad dynasty’s province and one-time stronghold, many fear the takeover marks the start of something far worse: a cycle of impotence and repression that will leave them as losers. in the new Syria.

Despite the widespread happiness across the country, Latakia’s coast is home to many from Assad’s minority Alawite sect and others who – either by choice or desperation – include soldiers and loyalists. which helped support the family’s brutal minority rule.

In the weeks since Assad’s fall, some have closed shops, stayed at home or gone into hiding amid a security vacuum and stories of revenge killings and attacks on minorities.

“I didn’t dare to go because I was worried about the roads,” an Alawite former security official said of the settlement centers. “They will kill us on the way there, or in our villages.”

There is currently little documentation of retributory violence, with the new powers-that-be dismissing reports as “isolated cases”. Traifi, asked about the rumored instances of people at checkpoints harassing Alawites and demanding that they curse the former president, said that kind of trouble does not represent the new government.

“But there are people manning checkpoints who have lost children, wives, family members due to bombings and fighting, whose friends are lost in prison. There is pain in their hearts,” he said. “We suffered them for 14 years. They can put up with us for a while. “

Some soldiers lining the residential center of Latakia appeared cautiously welcoming the prospect of a new start, a sign of how disillusioned even nominal loyalists are.

A 29-year-old former soldier said he was repeatedly barred from visiting his home on leave last year as Assad’s weakening grip on the country and its withering economy led to growing fears that the soldiers leave.

“Our life is the army, we have not learned how to do anything else,” he said, adding that he was not worried about security. “We’ve wanted this for a long time. In this new phase, they just want us to live our lives. “

But Traifi said that perhaps only 30 percent of those who arrived at the settlement centers turned in their weapons, adding that an intelligence unit was working to identify and attack those who still held their arms. Even the former state security employee acknowledged that both sides have weapons and that, without comprehensive disarmament, “we will have massacres within two months”.

Before Bashar al-Assad’s father Hafez rose to power in 1970, the Alawites were one of the poorest groups in Syrian society: families sent their daughters to clean houses in the big cities and their sons in the military to ensure they are provided with food and a steady income.

But during its rule, the Assad family elevated a select group of Alawite loyalists to positions of high authority, giving them preferential treatment above all others. Resentment of the brutal enforcement of practices to ensure they have wealth, power and political status disproportionate to their numbers was one of the main drivers of the 2011 protests that led to the civil war.

But on the eve of Assad’s fall, with most Alawites now facing an uncertain future, thousands have fled the capital Damascus to their ancestral homes.

The former state security employee said he received a call from his superior around midnight, telling him to pack his things and go home. He describes apocalyptic scenes: civilians and exhausted men fill the streets on foot and in cars, their abandoned weapons scattered by the roadside. “I parked on the right side of the road to Homs, and threw my gun into the waterway,” he said.

The two-hour drive to his village on the border with Lebanon took about eight hours on bumpy roads. He then took shelter at home, knowing that the men from his village who had been exiled to Lebanon after joining the rebels had now returned. He fears that those people are now preparing to take revenge against those they accuse of massacring their friends and family.

“There is no supervision or security here, so no one can stop the revenge killings,” he said. “There’s just no one here.”

A tense silence has hung in the air in Alawite villages and towns since Assad’s fall. Schools are open but empty. When asked if one was operating, a groundskeeper said: “Yes, the only thing missing is the students.”

In the birthplace of the Assad clan in Qardaha, unlike the big cities, the green rebel flag is almost nowhere to be found. The interior of Hafez al-Assad’s mausoleum is covered in soot from the fire that burned his resting place, while outside curses are painted against him and his wife.

Such attacks on the mausoleum have become “a kind of pilgrimage” for rebel supporters, said one resident.

But the Alawite elite that benefited from the Assads’ rule is a minority within a minority. Others within the wider Alawite community remain some of the poorest in Syrian society, many fearing the same people who committed crimes against the rest of the country.

A 40-year-old Alawite resident of Qardaha, who asked to be known only by his nickname Nana to avoid reprisals, described how people in the town live their whole lives in fear of their masters, who abuse people from their own sect and treat them with contempt. .

“They want us to stay (poor) so that people will continue to enlist in the army,” Nana said.

Nana and her sister teach in schools where children cannot afford the meager price of government textbooks, while her brother-in-law has spent the last 14 years avoiding military service.

But despite their dismay at the Assads, minorities such as the Alawites and Christians fear not only for their safety but that the new rulers will impose a new and unfamiliar social order.

Nana’s family makes and sells alcoholic beverages including arak and wine, which are not banned under the Assads, and like others, they borrow money to save before December, the poorest time of the year. . But when they woke up to the news that the Assad regime had fallen to the Islamist HTS, the family went to pack up their supplies and took down the store’s sign as a precaution.

When Nana’s husband later asked an armed man patrolling the town if he could reopen, he was told that selling alcohol was forbidden in Islam. The family, like others, is awaiting clarification from the new government on what is legal and what is not.

“We bought stock like crazy and now it’s sitting in our stores,” his brother-in-law said, adding that his nephew was told off by another patrolman for wearing pajamas outside.

While they suffered “humiliation” under the Assads, he said, they learned how to maneuver under the regime. “Now, we don’t know what (type of regime) we have,” Nana said.

Cartography by Aditi Bhandari