Yogita LimayeSouth Asia and Afghan correspondent

Aakriti Thapar / BBC

Aakriti Thapar / BBCWhile Shahnaz was working, her husband Abdul called a taxi and took them to the only medical facility they could use.

“She was in pain,” he said.

The clinic is a 20-minute drive from the hotel, and is located in Shesh Pol Village in the Badakh Mountain province of northeastern Afghanistan. This is where their two older children were born.

Abdul sat next to Shahnaz to comfort her as they drove over the gravel road for help.

“But when we got to the clinic, we found it was closed. I didn’t know it was closed,” he said.

Warning: Readers may find some details in this article that are frustrating.

Shesh Pol’s clinic is one of more than 400 medical facilities, and one of the poorest countries in Afghanistan is one of the world’s poorest countries after the demolition of the United States’ International Development Agency (USAID).

The Shesh Pol Clinic is a single-story structure with four small rooms with white paint peeling off the walls, Soviet posters are full of information and guidance on pregnant women and new mothers.

Aakriti Thapar / BBC

Aakriti Thapar / BBCIt doesn’t look much, but in the mountains of Badakhshan, the lack of access is a major cause of historically high maternal mortality, the clinic is a key lifeline as part of a broader plan implemented by the country during its US-backed government to reduce maternal and newborn deaths.

It has a trained midwife who assists with 25-30 delivery per month. It has a batch of drugs and injections and also provides basic medical services.

Other medical facilities are too far from the village of Abdul, and Shahnaz traveling on bumpy roads is not without risks. Abdul also has no money to pay for a longer trip – the taxi rental cost 1,000 Afghanistan ($14.65; £12.70), about a quarter of his monthly income as a labourer. So they decided to return home.

“But the baby is coming, we have to stop by the road,” Abdul said.

Shahnaz transported the baby girl in the car. Not long after, she passed away, bleeding heavily. Their children died a few hours later, before she was named.

Aakriti Thapar / BBC

Aakriti Thapar / BBC“I cry and scream. If the clinic is open, my wife and children can be saved,” Abdul said. “We have a hard life, but we live together. I’m always happy when I’m with her.”

He doesn’t even have Shahnaz’s pictures to keep.

If mothers and babies are treated in clinics, mothers and babies will not be able to survive, but without it, they will not have a chance, highlighting the undeniable impact of U.S. aid cuts in Afghanistan.

The United States has been Afghanistan’s largest donor for decades, with U.S. funds accounting for a staggering 43% of all aid in the country in 2024.

The Trump administration has proven to withdraw it, saying “there are credible concerns that funding benefits terrorist groups, including…the Taliban, to rule the country”. The U.S. government further added They have reported At least $11 million has been “stolen or enriched the Taliban.”

Reports cited by the U.S. State Department It was produced by the Special Inspector General of Reconstruction in Afghanistan (Sigar). It said U.S. Agency partners paid $10.9 million in U.S. taxpayer funds to the Taliban-controlled government as partners “tax, expenses, tariffs or utility.”

The Taliban government denied that aid funds were in their hands.

“This allegation is incorrect. Aid is provided to the United Nations and through them provide assistance to NGOs in the provinces. They identify who needs assistance and they allocate the assistance themselves. The government is not involved.”

The Taliban government’s policies, especially its restrictions on women, are the toughest policies in the world, which means that after four years in power, it is still recognized by most people in the world. This is also a key reason why donors are increasingly leaving the country.

The United States insists that no one died from aid cuts. Shahnaz and the baby’s deaths were not recorded anywhere. Not countless, either.

The BBC has recorded at least six devastating accounts in areas where USDA-backed clinics are closed.

Next to Shahnaz’s grave, the villagers gathered around us pointed out the other two graves. They tell us both are women who died in childbirth in the past four months – Daulat Begi and Javhar. Their babies survived.

Not far from the cemetery, we meet Khan Mohammad, whose wife, Gul Jan, 36, died five months ago while giving birth. Their baby boy Safiullah died three days later.

Aakriti Thapar / BBC

Aakriti Thapar / BBC“When she gets pregnant, she goes to the clinic for check-ups. But during pregnancy, she closes. During labor, she suffers a lot of pain and blood loss,” said Khan Mohammad. “My kids are always sad. No one can give their mother’s love. I miss her every day. We live a sweet and loving life together.”

About five hours drive from Shesh Pol Cawgani is another village closed by a clinic backed by USAID, Ahmad Khan, the grief father of Maidamo, showed us their room in their mud and clay home, and she died and gave birth to the baby Karima.

Aakriti Thapar / BBC

Aakriti Thapar / BBC“If the clinic was open, she might have survived. Even if she passed away, we wouldn’t regret knowing that the medical staff did their best. Now we regret and suffer. America has done it for us.”

Bahisa is in another alley and tells us how horrible it is to give birth at home. Her other three children were born in the Cawgani clinic.

“I’m scared. In the clinic, we have midwife, medication and injections. I have nothing at home, no pain medication. It’s unbearable pain. I feel like life is life. I’m becoming numb.”

Her baby girl is named Fakiha and died three days later.

Aakriti Thapar / BBC

Aakriti Thapar / BBCThe closure of clinics in the village has led to a surge in patients in the obstetric wards of the main regional hospitals in the provincial capital Fasabad.

Up to this point, there are risks through the dangerous landscape of Badakhshan. A horror photo of a newborn baby who was given birth on his way to Faizabad, whose neck was snatched out before he arrived at the hospital.

We visited the hospital in 2022, and although it was extended at the time, the scene we saw this time was unprecedented.

On each bed, there are three women. Imagine having started working, or having just experienced a miscarriage, not even lying in bed.

Aakriti Thapar / BBC

Aakriti Thapar / BBCThis is what Zuhra Shewan, who suffered from miscarriage, had to endure.

“I bleed badly and didn’t even have a place to sit down. It’s really hard. When the bed is free, women can bleed.”

“We have 120 beds in the hospital. Now we admit 300 to 305,” said Dr. Shafiq Hamdard, director of the hospital.

Although the patient’s burden was swollen, the hospital’s funds were also cut sharply.

“Three years ago, our annual budget was $80,000. Now we have $25,000,” Dr. Hamdard said.

By August this year, as many maternal deaths were recorded as last year’s overall record. This means that at this rate, maternal mortality may increase by as much as 50% compared to last year.

In the past four months, neonatal deaths have increased by about one-third compared to the beginning of the year.

Razia Hanifi, the head midwife at the hospital, said she was exhausted. “I’ve been working for the last 20 years. This year was the hardest because of overcrowded, shortage of resources and a shortage of trained staff,” she said.

Aakriti Thapar / BBC

Aakriti Thapar / BBCHowever, due to the Taliban government’s restrictions on women, there was no reinforcement. Three years ago, all higher education (including medical education) were banned from the use of women. Less than a year ago, in December 2024, training for midwives and female nurses was also banned.

In a cautious location, we met two female students who were being trained when the training was closed. They don’t want to be determined for fear of retaliation.

Anya (name change) said that when the Taliban took over, they were both in graduate programs at the university. When they closed in December 2022, they started midwife and nursing training because it was the only way to get education and work.

“I became depressed when that was also forbidden. I was crying day and night, and I couldn’t eat. It was a painful situation.”

Karishima (name change) said: “Afghanistan has already lacked midwives and nurses. Without more training, women will be forced to have children at home, which puts them at risk.”

We asked Suhail Shaheen, the Taliban government, how they could prove that the ban effectively curbs the health of half of the population.

“It’s our internal problems. These are our issues, how to deal with them, how to think about them, how to make decisions, it’s internal. It depends on leadership. They will make decisions based on the needs of society.”

As their access to medical services is severely limited, the wave of Afghan women’s right to health and life itself is squandered.

Other reports, optics and videos: Aakriti Thapar, Mahfouz Zubaide, Sanjay Ganguly

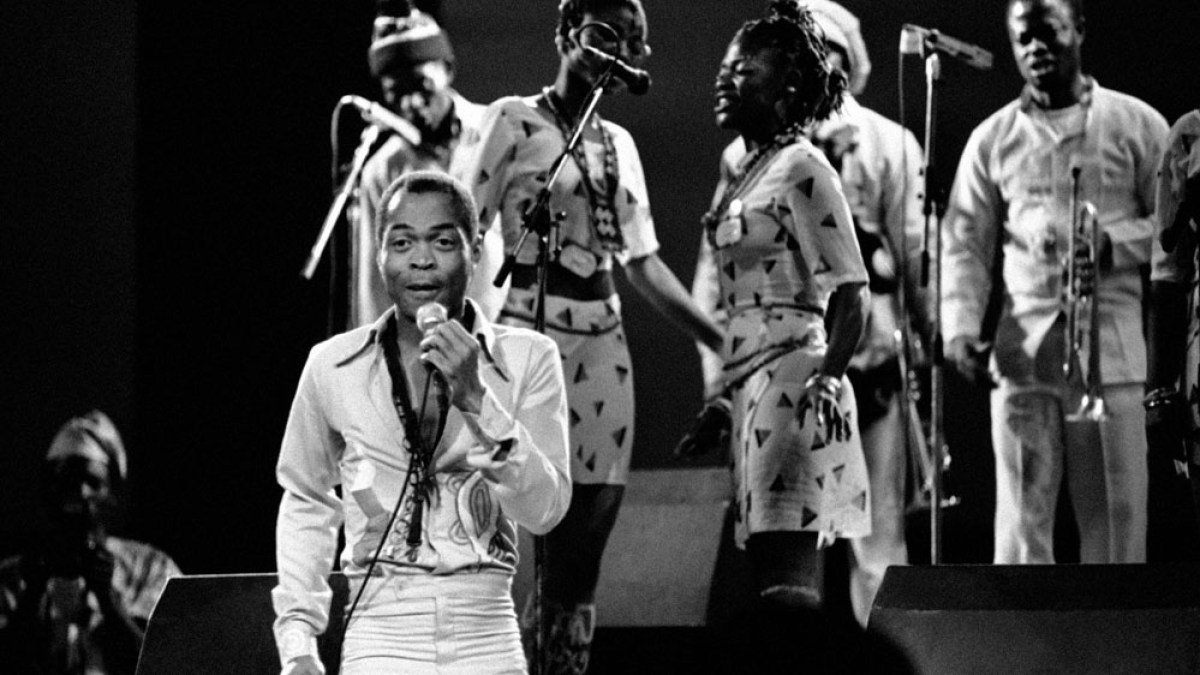

The top image shows Abdul with his daughter and son in Shesh Pol.